The “Reviewing the Past” series of sharing sessions is the first themed activity organized by the archive since its establishment and will also be an ongoing long-term project. Starting from Chengdu, it will expand to various regions across China and ultimately aim to compile and preserve the history of performance art across different regions worldwide. Through inviting experts, eyewitnesses, and audiences to share stories, engage in dialogue, and discuss, the “Reviewing the Past” initiative seeks to gain a broader perspective on the future by reflecting on history.

Since the launch of the “Looking Back” project, the process of collecting and organizing documents has often yielded new discoveries, evoking feelings of nostalgia for the passage of time and the weight of history. The wealth of information uncovered continues to challenge and redefine people’s existing perceptions and experiences. This once again underscores the urgency and necessity of collecting and organizing performance art documentation archives—a long-neglected area within China’s contemporary art field. After all, the first generation of artists who pioneered performance art exploration in mainland China during the 1980s are now mostly elderly, with some having passed away quietly, and many primary sources are no longer accessible.

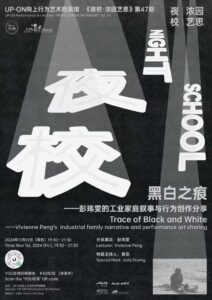

On the evening of September 27, 2022, at 8 PM, the tenth installment of “Reviewing the Past” titled “Yunnan Performance Art Archive” was held at the archive. The sharing session was hosted online by artist and curator He Libin. When it comes to performance art in Yunnan, we often joke that Yunnan is China’s “performance art powerhouse.”

The reason for this is twofold: first, Yunnan has produced many important performance artists, such as Zhu Fadong and He Yunchang; Second, since the 1990s, performance art creation in Yunnan has been continuous, with artists from various regions both domestically and internationally creating a large number of performance art works in Yunnan. This makes Yunnan one of the few regions in China with a thriving performance art ecosystem, thanks to the long-term efforts of He Libin and his colleagues. In 2009, a significant turning point in the development of performance art in Yunnan, He Libin founded the “In the Clouds International Live Art Festival” in Kunming.

The festival attracted and invited numerous artists from home and abroad to Yunnan for exchange and creation, establishing an international platform for performance art exchange and significantly enhancing the vitality of performance art in Yunnan. Although He Libin is well-versed in the history of performance art in Yunnan, the history of performance art in Yunnan is long and complex, with many materials and information requiring extensive collection and verification. Additionally, the volume of artistic activities and works is enormous, making the work extremely time-consuming and labor-intensive.

We extend our gratitude to friends such as Luo Fei, Zhu Fadong, He Yunchang, and Xin Wangjun, who either patiently participated in verifying and organizing the information or provided historical documents and literature on performance art, enabling us to complete the collection and organization of the materials within the scheduled timeframe and ensuring the smooth conduct of the sharing session.

Review

preview

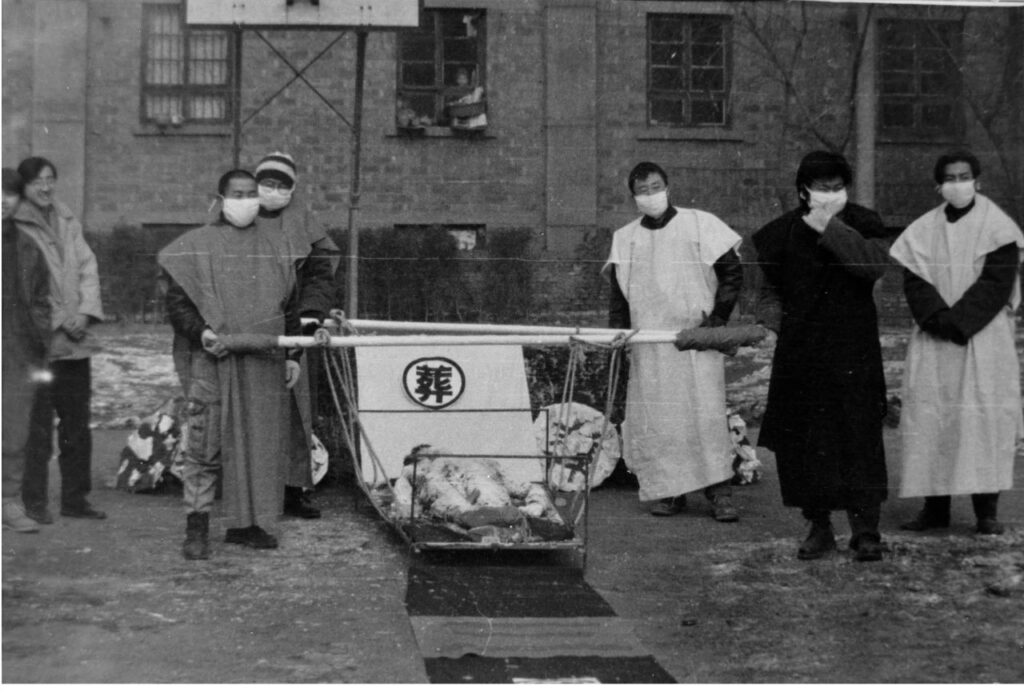

In the eleventh installment of “Reviewing the Past,” we shift our focus to Gansu. Performance art in Gansu dates back to the 1980s, but it was the “Lanzhou Art Troupe,” active in the early 1990s, that gained prominence in the art world. In 1992, works such as “Burial,” created and performed by Ye Yunfeng, Yang Zhichao, Cheng Li, Ma Yunfei, and Liu Yiwu, were produced.

The process of the work is documented in the relevant text as follows: “Held in Lanzhou from December 1992 to January 1993, the work involved the burial of a painter who had long colluded with art dealers, editors, and those who manipulated personal relationships, and who had sold his paintings. The performance included the distribution of ‘death notices’ and ‘obituaries’ via newspapers, letters, telegrams, and street posters; the creation of a corpse model; setting up the event scene, parading the corpse through the streets, burning it, burying it, and sending a box of belongings to art critics and artists.“ Looking back, ‘Burial’ might have been the work most likely to influence the nation, but the reality was different. This work by the ”Lanzhou Group“ seemed to mark the ”end” of modern art in Lanzhou, and the city remained outside the radar of Chinese contemporary art thereafter.

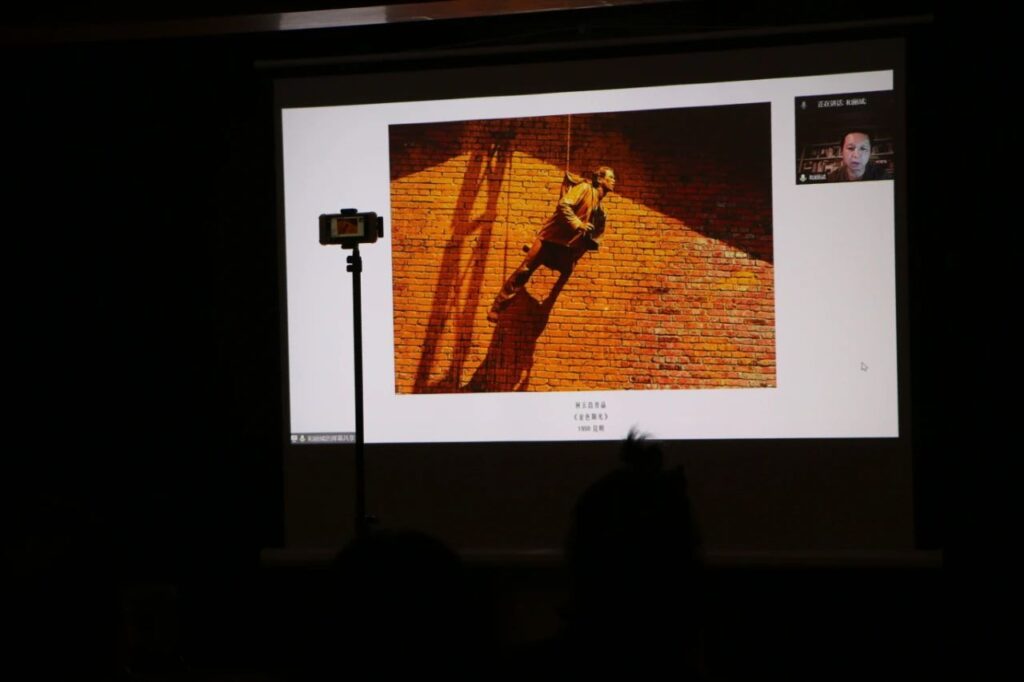

This situation began to change gradually after 2004. This was largely due to artist Jin Le establishing the Shijiezhuang Art Museum in Shijiezhuang Village, Tianshui. Subsequently, institutions such as the Lanzhou Grain Warehouse Contemporary Art Museum, Gaodunying Art Festival, Northwest Minzu University, and Cube Art Museum became driving forces behind the revitalization of performance art in Gansu. A significant number of local young artists began to emerge, including Nian Jinjun, Mou Songtao, Zhao Jinlong, Chu Bingchao, and Zhang Qiong. In this review of Gansu performance art, we have uncovered the 1981 work by artists Li Waku and Yang Zhichao, titled “We Escape the Gobi Desert Together,” created on the Gobi Desert near Jiayuguan North Station (regrettably, no visual records remain). The process involved manually retrieving unnamed skeletal remains from decaying wooden boxes, placing them in cardboard boxes, then sneaking onto a green-painted train with the remains to evade fare payment to Jinan, and subsequently assembling the fragmented bones into a complete human skeleton at a medical college. Based on the currently known records of performance art in mainland China, this work may be the earliest performance art creation by a mainland artist. Most previously documented performance art works in mainland China occurred around 1985.

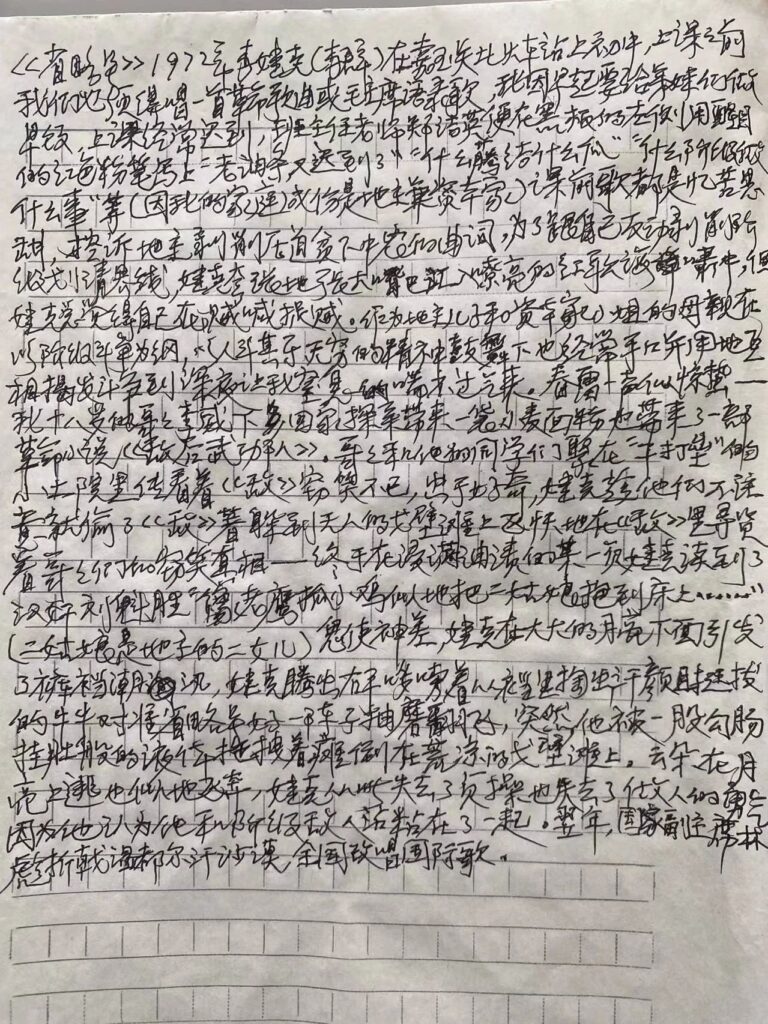

During the process, artist Li Wake mentioned that in 1972, he began questioning the human condition through his work “Ellipsis,” which became the starting point for his subsequent artistic creations. However, since this work is based on the artist’s own “oral history” and lacks photographic documentation or witness verification, in accordance with archival documentation standards, we have archived Li Waku’s “oral history” manuscript but have not formally included it in the Gansu Performance Art Chronology at this time. Art critic Lu Mingjun wrote in his article “Modern Art in Lanzhou in the 1980s”: “Oral history” inherently carries a certain degree of criticality.

Every witness inevitably intertwines varying degrees of critical consciousness during the process of recollection. Of course, historical writing is often the result of subjective criticism. Especially when it involves the interests of the subject or personal privacy, the narrator consciously avoids discussing it or offers an alternative interpretation. I believe this is precisely the limitation of “oral history.” “Words alone are not evidence,” and facts that originate solely from personal accounts remain suspect, at least unable to be fully affirmed. Moreover, we often encounter situations where different parties involved in the same event present conflicting facts and attitudes. This means that oral history is inherently uncertain until the day when authentic historical records are discovered to serve as evidence, at which point we may construct a possible framework.

From this perspective, given the scarcity of documentary materials regarding the development of modern art in Lanzhou during the 1980s, all we can do is present the interviews with over twenty eyewitnesses as they are, even if they contain contradictions and conflicts. The accuracy of these accounts is not my concern; let history be the judge. On the evening of October 29, 2022, at 8 PM, the eleventh session of “Reviewing the Past” will be held at the Archives, titled “Gansu Performance Art Archives.” We are honored to have artist Yang Zhichao host this sharing session. During the session, pre-recorded video interviews with some artists will be played, helping everyone gain a more vivid and in-depth understanding of the artists, their works, and the state of performance art in Gansu. The extensive documentation of performance art on display at the venue will further enrich attendees’ understanding of Gansu’s performance art scene. Finally, we would like to express our gratitude to the many colleagues who provided leads and collaborated in the compilation of this documentation, including Yang Zhichao, Li Wake, Cheng Li, Ma Qizhi, and Zhang Hongwei. We also extend our heartfelt thanks to Yang Junfeng for his tremendous efforts in collecting and organizing the materials.

Burial, 1993 / Collective work by the Lanzhou Army / Lanzhou

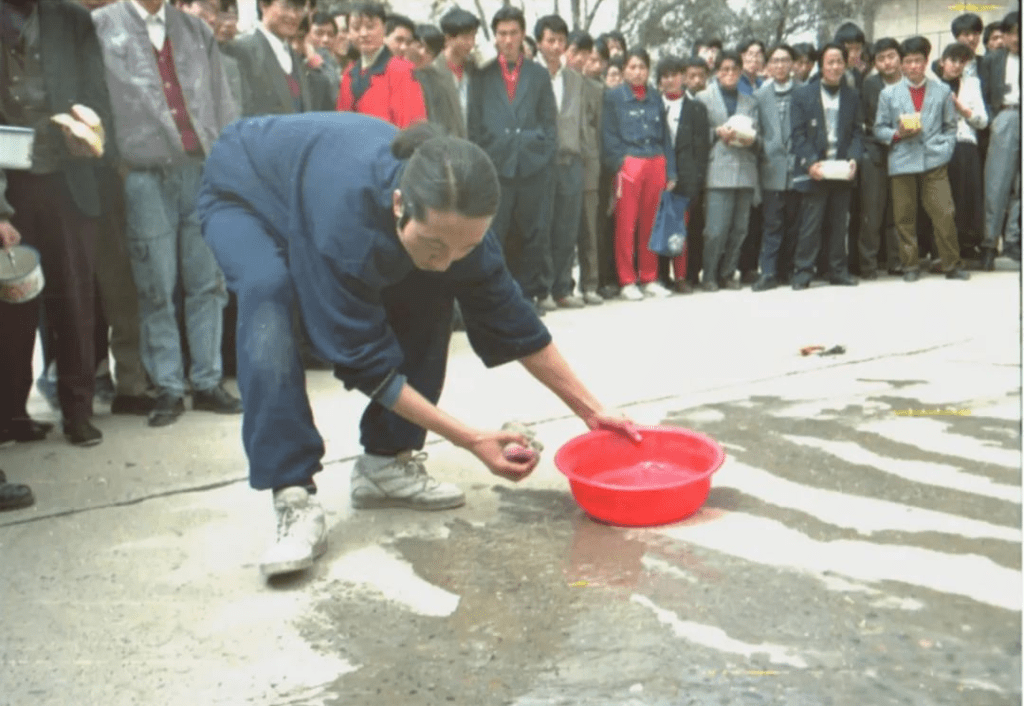

Rolling Canvas / May 4, 1987 / Yang Zhichao, Xichuan, etc / Wushan Park, Lanzhou

“Paying Close Attention to a Nine-Square-Meter Piece of Ground” / 1994 / Ma Qizhi / Lanzhou

Ellipsis / Li Wake

Planting Days / Liu Xinhua / May 3, 1995–February 14, 1997