The Research Room section of UP-ON Art Archives focuses on revitalizing archival materials through theoretical research, seminars, self-publishing, and other initiatives to foster in-depth knowledge production.

Body Speech and Imagining the Other: People and Events in

Xining Performance Art

On the first Sunday of June 2010, poet Zhang Zheng was the sole artist to present a work during the open day of the “Possibility” Performance Art Workshop. The event took place in a rented room in the suburbs of Xining. Under the intense sunlight streaming through the windows, Zhang Zheng gazed intently at the patterns of light and shadow cast upon the floor. As the light shifted angles gradually, he made subtle adjustments to his posture, absorbed and transfixed in the empty room. The only individuals witnessing the entire process were Xue Kaihua, who was filming that day, and a single spectator.

The “Possibility” workshop was co-founded by Xue Kaihua and myself in July 2009. Using performance art as its primary medium, it regularly convened local artists to create works on the first Sunday of each month. We posted open house information online to encourage non-artist audiences to observe and discuss.

Zhang Zheng’s performance that day was one of only two sessions in over two years with the smallest audience. The other instance was artist Li Yicheng’s piece—he spent an hour repeatedly rubbing a specific section of a large tree trunk with his hands. The sole spectator was a teenager who crouched motionless on a nearby hilltop, watching intently for the entire hour. After the performance ended, the boy stood up and left. I desperately wanted to ask him, “What did you see?” but never got the chance to speak.

Li Yicheng’s Work

From an artist’s perspective, even with only one viewer, such a performance holds no fundamental difference from a crowded gallery exhibition. The intensity and piercing quality generated by the spectator’s gaze remain unchanged. Art demands to be seen, and performance is no exception—whether live or recorded. So for whom, then, is performance created? This timeless artistic question serves as the opening to this essay. It concerns the imagination of the “other” among creators on this land. This “other” may not exist within specific spatiotemporal coordinates, yet it carries genuine weight within the artist’s creative impulse.

The Initial Stage

On March 23, 2000, Chang Yao, unable to bear the torment of illness, leaped from the upper floors of Qinghai Provincial People’s Hospital. Like his poetry, he unleashed the heavy force of life’s suffering crashing into the earth’s core. A light that had illuminated Chinese poetry throughout the 1980s and 1990s suddenly dimmed. Yet Xining remained largely undisturbed. This city, tucked away in a remote corner, seemed to follow its own rhythm, perpetually maintaining its unique slowness and tranquility. Art followed suit. While many cities across the country were swept up in a fervent wave of cultural and artistic fervor during those decades, Xining remained as still as deep water, silent and unruffled.

In 2004, artist Liu Chengrui staged his first performance art piece on the Qinghai Normal University campus, centered on environmental protection. Compared to his current work, it felt somewhat raw, yet the true value lay not in language or rhetoric, but in the direct impact of the space and the body. The raw power pierced through the somber gazes around him, striking the spiritual core of many. This marked Xining’s first live performance art event.

In June 2005, as graduation approached, Liu Chengrui and I co-curated the conceptual art exhibition “What Is This…?”—Xining’s inaugural contemporary art show—held on Wenmiao Street. On opening day, crowds gathered before the Confucian Temple as Liu Chengrui performed his piece Marrying Confucius. Dressed as a woman, he and Confucius (played by collaborator Lao Wang) staged a traditional Qinghai wedding ceremony before the temple. By “marrying” Confucius as a husband within the Confucian Temple—one of the most symbolically charged sites of Confucian culture—the performance parodied the disciplinary control exerted by ritualistic ethics and orthodox ideology over the body and identity. The absurdity of this humorous ritual, intruding into sacred narratives, plunged viewers into discomfort, confusion, and even uproarious laughter. During the exhibition opening that day, sixteen-year-old artist Ma Yi also performed his work spontaneously on-site. He and his collaborator wore simple masks, one holding a banknote and the other a wine bottle, kneeling on the ground with their backs to each other. The work pointed directly to the prevailing atmosphere of restlessness and values of the times.

Marrying Confucius, Performance , 2005, Liu Chengrui

That same bitter winter, Liu Chengrui covered himself in mud, clutching a white balloon, and walked barefoot for nearly six hours around Xining. The stark contrast between his mud-covered body and the pristine white balloon created a powerful tension against the gray winter streets. His feet left imprints on the frozen pavement as he brushed past passing vehicles and pedestrians. Within this sorrowful sense of alienation lay another dimension—a profound melancholy for the land, a fairy-tale surrealism, and an almost ascetic endurance of the long walk. The work blends warmth and cruelty, juxtaposing physical pain with poetic symbolism. It is rooted in the weight of reality yet carries a thread of light, imaginative flight.

Barefoot, Performance , Xining, December 24, 2005, Liu Chengrui

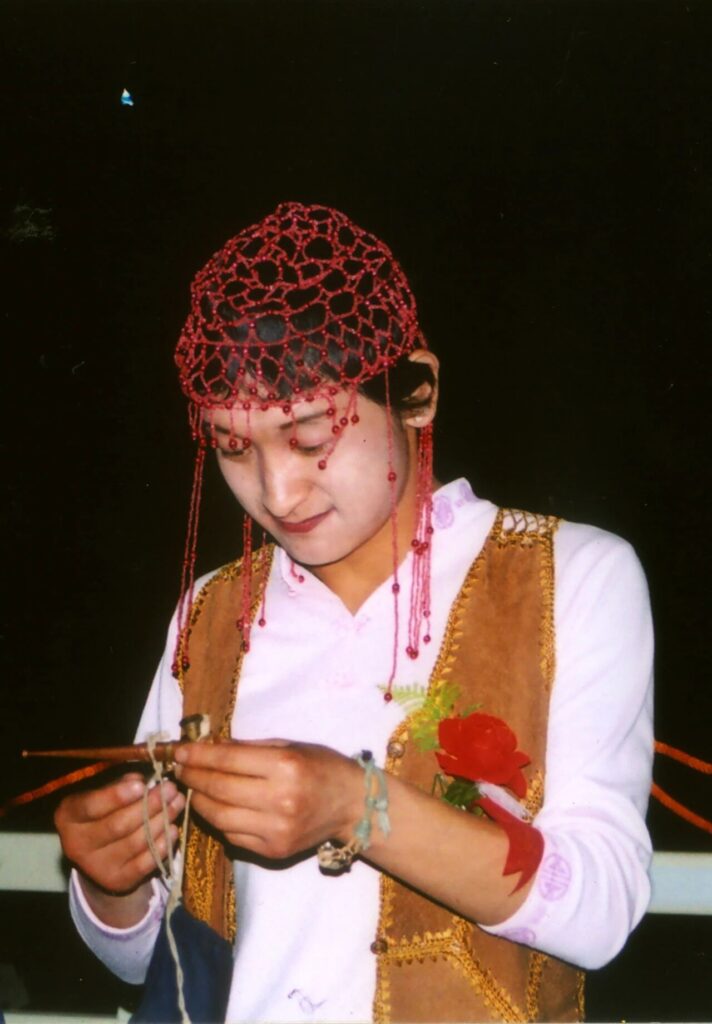

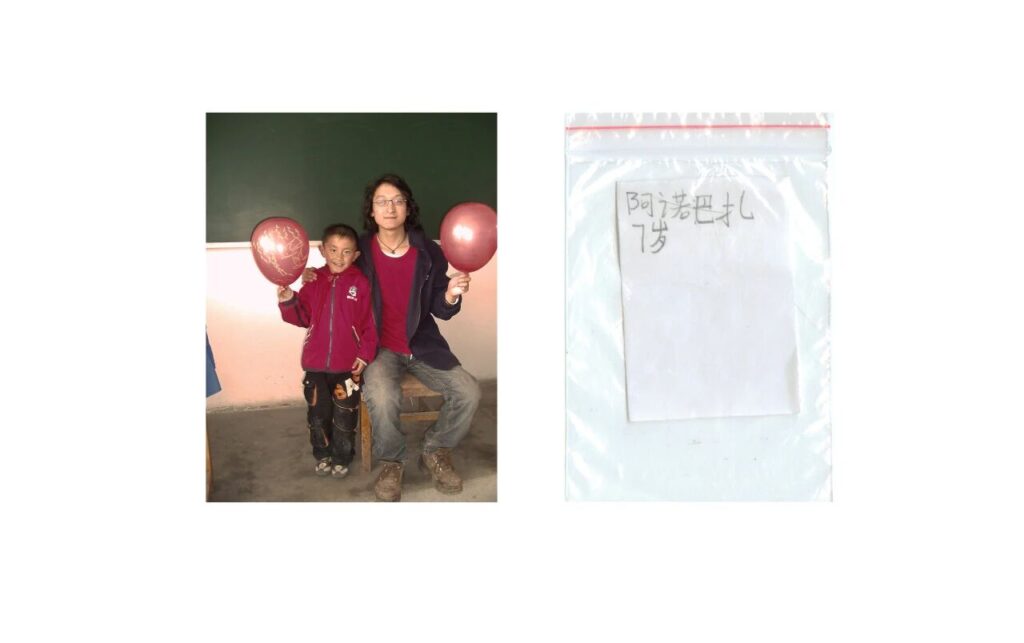

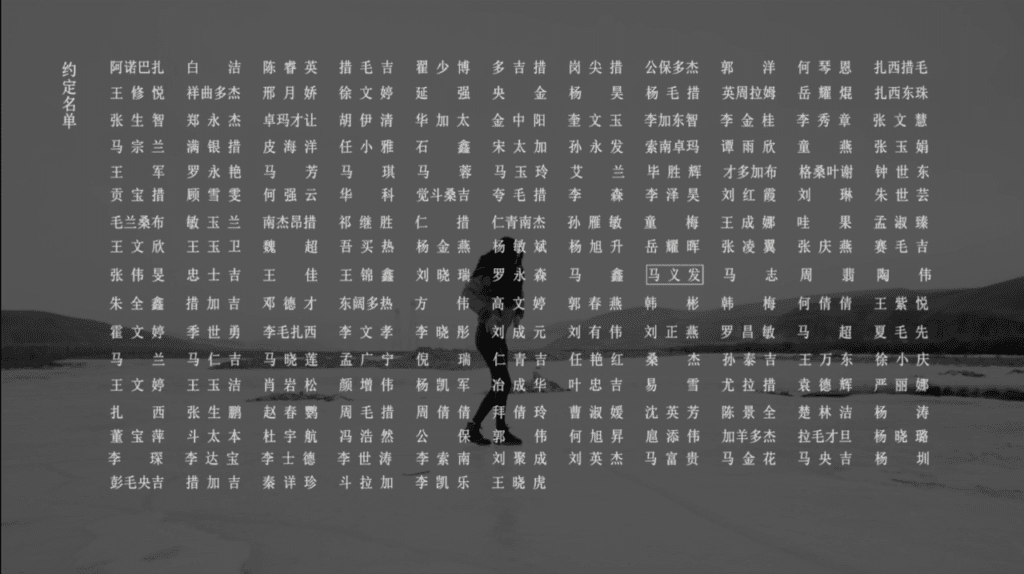

In 2006, Liu Chengrui traveled to Gangcha County on the shores of Qinghai Lake to teach for a year, launching an artistic project that continues to this day—The Ten-Year Plan. At a pastoral elementary school over 3,000 meters above sea level, the artist established a simple yet solemn pact with 187 children: capturing their faces with a camera, exchanging locks of hair as tokens, and pledging to reunite every decade. This seemingly simple ritual gradually unfolds extraordinary tension over time. Nearly two hundred parallel life trajectories resonate and intersect continuously through this artistic pact. With restrained, masterful artistic language, The Ten-Year Plan achieves a poetic inquiry into time and memory. The sealed locks of hair and periodically updated group photos become unique yardsticks for measuring the depth of life. In this project, Liu Chengrui continues the physical intervention characteristic of performance art while extending his reach into the vast landscape of lived experience. Within the crevice between art and reality, he carves a long-flowing stream exploring growth, transformation, and commitment. After completing his teaching service, Liu Chengrui left Qinghai to live and work in Beijing.

Ten-Year Plan Archives—Anobazah 2006, Liu Chengrui

Ten-Year Plan Archives—Anobazah 2016, Liu Chengrui

Ten Years, Video Screenshot 2006–2016, Liu Chengrui

As artists who left Qinghai early on to create in the Yuanmingyuan Artists Village, Hei Yue (Ji Shengli) and Shao Yinong also practiced in Qinghai around 2004. Shao Yinong used Qinghai’s mountain villages as sites for his work, mobilizing hundreds of students to wave red flags amidst the typical barren western mountain landscapes. The piece resembled performance art imbued with potent collectivist memory. Hei Yue, meanwhile, continued his long-term project Buttocks 123, primarily employing performance video as its medium. Initiated on December 30, 2001, in Akashi City Park, Japan, the work unfolded across various countries and locations including Japan, the United States, South Korea, and China. In 2005, filming took place at the Ta’er Temple in Qinghai.

During this period, performance art practices also began to emerge locally within Xining.

Six Slices

During the inaugural workshop open day in 2009, artist Jia Yu performed his work Intimacy. Wearing a hood stitched with magnets, he crawled slowly across a floor littered with iron shavings, nails, razor blades, and bullet casings. As he moved, the metal fragments continuously adhered to his hood. The hood’s concealment can be interpreted as the artist deliberately obscuring individual identity, symbolizing a broader, universal human condition. Yet as a friend of Jia Yu, I know that beneath this hood filled with cold, sharp metal lies a person who is soft and warm in daily life, yet acutely sensitive to the sharp edges and hostility of reality. Regarding his circumstances, Intimacy serves as a response. Born and raised in Yushu, Qinghai, Jia Yu’s early footage of Tibetan regions stemmed from his experiences living in pastoral areas. This connection with the land and nature may well be the source of the inclusive spirit found in his work. Another crucial dimension of his work often centers on the alienation stemming from societal distortions and oppression. Examples include applying feminine makeup to half of Uncle Wu’s face in their collaborative piece, or strapping cameras all over his body while projecting the live footage onto a screen at the venue—using the interwoven darkness of the space to suggest power dynamics. One piece continues to surface in my memory over the years: in 2010, during the Guyu Action performance art festival in Xi’an, Jia Yu presented a work titled Home. He lay prone on the ground while a collaborator piled earth atop his head to form a small house, continuing until oxygen deprivation caused suffocation and he could no longer endure. Jia Yu constantly oscillates between tenderness and rupture, constructing nuanced and multi-layered expressions.

The complex systems of reality often project their multidimensional intricacies through the individual as the terminal point. Within this framework, the individual is not merely a carrier of information but also an embodiment of these complexly intertwined forces—forces that continually flash through the artist’s work.

Intimacy 2009, Jia Yu

《The Faint》 Jia Yu

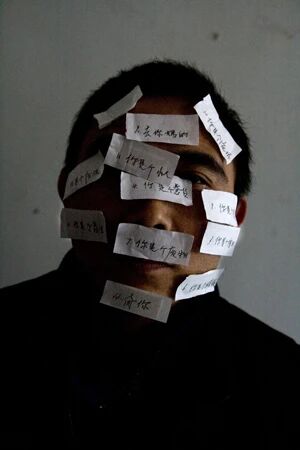

The intense anxiety stemming from reality within artist Ma Wu is continually transformed into repeated counterquestions. At his first open house event, unable to conceive of a piece to create, Ma Wu enacted anxiety itself: persistently banging his head against the wall, incessantly scraping his fingers against the surface to produce sharp sounds. At another open house, he asked attendees to write highly offensive remarks on slips of paper, which were then read aloud and affixed to his face until it was entirely covered. This might unconsciously evoke artist Zhang Huan’s work Genealogy, yet the two pieces differ fundamentally in their core essence. Zhang Huan explores the relationship between family lineage and individual will within Confucian tradition, while Ma Wu reflects the more immediate, everyday realities of individual existence and its vicissitudes. This attempt to convey inner conflict, pain, and emotional turbulence—directly presenting the constriction of the spiritual world—is fundamentally an expressionist performance. Expressionism focuses on the intensity of emotion and the essence of life, rather than rational or naturalistic precision. On one hand, it uses intense artistic language to reveal the anxiety, alienation, and estrangement of human existence; on the other, it questions the rebellion against existing artistic language. During the workshop, Ma Wu engaged in multiple anti-performance practices: standing motionless for ten minutes in each of a room’s four corners (Corners); sticking out his tongue for several minutes toward each cardinal direction outdoors; sitting in one spot for five minutes before declaring his right big toe had twitched over two hundred times. Clearly, the two-year workshop had cultivated a certain inertia and deliberate artifice, with Ma Wu using his work to articulate his skepticism and critique.

If Ma Wu’s anti-performance stems from an examination of performance itself, the anti-performance in Zhang Zheng’s work arises from his self-awareness as a poet. Having never received formal training in visual arts, Zhang Zheng possesses a natural immunity to the visual. He approaches his work from internalized sensations, emphasizing the relationship between bodily perception and space or material. Examples include touching an invisible yet palpable colossal object within a space; rubbing a wall with one’s body; and the work mentioned at the beginning of this article. These actions resemble entering the world he habitually depicts through poetry. Yet for viewers accustomed to visual observation, these abstract individual sensations prove difficult to access. Beyond the sensory level, even in his relatively concrete works, he strives to reflect on his poet identity through art: standing barefoot on a sheet of white paper while improvising poetry, with an assistant continuously pouring water over his head until the poem is completed. His practice perpetually navigates the boundary between language and action. As a poet by origin, he transforms perceptual experiences beyond words into a personal bodily grammar—those seemingly “anti-performance” acts of groping at emptiness or rubbing walls are, in fact, the embodiment of poetic metaphor into physical presence. In works like “Writing with Water,” he ritualizes the act of writing itself while creating an intertextuality between bodily sensations and improvised verses. Zhang Zheng is, in essence, an artist who writes poetry with his body.

Zhang Zheng’s Works

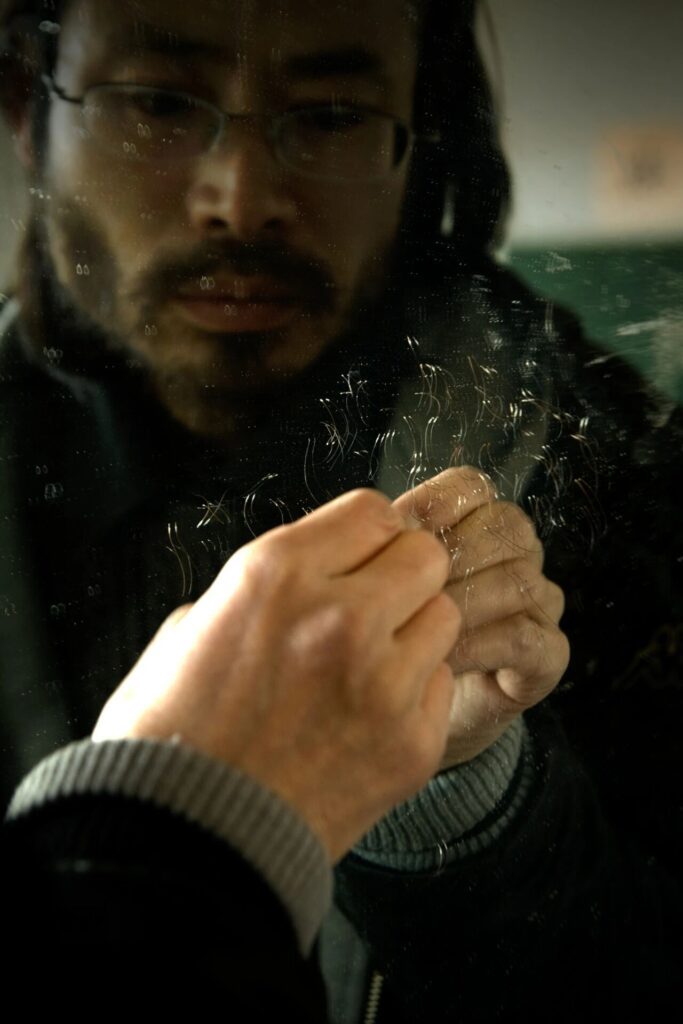

Xue Kaihua’s exploration, however, carries distinct academic aspirations. Having studied philosophy at Northeast Normal University, Xue grew disillusioned with the institution’s rigid educational methods and withdrew during his junior year to return to Xining. Despite facing extreme material deprivation, he maintained his passion for philosophical inquiry. During this period, Xue Kaihua became engrossed in Foucault’s philosophy of the body, examining how the body is disciplined, shaped, and controlled within power relations. Foucault posited that the body is not merely a biological entity but also a site where power operates. Through bodily actions and postures, individuals are socially constructed and managed, thereby forming mechanisms of self-monitoring and self-regulation. Performance art, as an art form using the body as its medium, could powerfully pierce through existing disciplinary structures and controls imposed upon the body. This understanding was not unique in performance art practices of the time. Influenced by body philosophy, many artists recognized that the body serves not only as a medium of expression but also as a revelation of social structures, power mechanisms, and internalized repression. Xue Kaihua conveyed his reflections through austere, poetic works: blindfolding himself and sanding his entire body with sandpaper; collecting a sack of late autumn leaves, spreading them on the ground, and repeatedly rolling over them with his body to crush them.

Xue Kaihua’s Work

Li Yicheng’s work 2010 was performed on New Year’s Day 2010. He stood before a mirror, plucking his beard hair by hair and counting each one, until he had removed exactly 2010 hairs. The seemingly mundane, minor pain of plucking hairs would not affect viewers. Yet when this commonplace act accumulates to a certain scale, it pushes the experience into an unsettling dimension. The artist uses his body as a measuring tool, making time tangible through each minute pain—the number 2010 ceases to be an abstract calendar year and becomes a real imprint etched into flesh. In Walking Mosaic, Li Yicheng enlarged a nude photograph of himself to scale, cut out the pixelated genitalia from the image, and pinned this fragment to his trousers with a safety pin while walking through public streets. When the enlarged mosaic fragment transferred from the photograph to the real body, the censorship symbol created an absurd dislocation with the actual flesh. The artist embodies the visual violence of the digital age, responding to mainstream visual taboos with a playful yet incisive approach. Li Yicheng is an exceptionally active and prolific artist whose works often employ extreme repetition, self-consumption, or absurdity to radically expose overlooked violence and discipline in reality.

Li Yicheng’s Work

Another exceptionally prolific artist is Dong Nu. In My 36, he laid a string of thousand-cracker firecrackers flat across an empty classroom and lit them. Covering his head with red cloth, he jumped around the ignited firecrackers in the manner of playing jump rope. The unconventional combination of space, body, and object lends a layer of innocent filter to the dangerous firecracker game. The lighthearted humor of the skipping rope routine is precisely the work’s subtlety—transforming the existential predicament into a playful spectacle where pain and childlike wonder coexist through gamified body language. Dong Nu is also an artist who immerses himself in wine. He once addressed his relationship with alcohol through a piece: an empty wine bottle placed in an empty corridor, tethered by a long string, while he pulled the string from a room at the corridor’s end. The bottle repeatedly struck the floor with each tug, its sharp, jarring echoes reverberating through the corridor. That piercing sound seemed like an inner interrogation from his psyche. The bottle, tethered by the long cord, functioned both as his alter ego and a symbol of desire. The transformation of everyday found objects often tests an artist’s imagination regarding the material itself and their insight into life. This perspective highlights Dong Nu’s lightness and wisdom in recoding everyday elements. Simultaneously, through these works, we witness the artist’s deconstruction and exploration of his inner world. What he presents to us is not merely a collection of artworks, but a vivid process of an artist engaging in dialogue with himself and with life.

My 36, 2010, Dongnu

Between 2011 and 2014, the Possibility Performance Art Workshop also hosted three editions of the “Micro-Body Speech” Performance Art Festival, inviting artists from Beijing, Chengdu, Xi’an, Taiwan, Japan, and other regions to Xining. This article focuses on briefly outlining the state of Xining’s local creators, so further elaboration on this point is omitted.

Conclusion

Reflecting on these individuals and events within Xining’s performance art scene, we return to the article’s opening question: For whom is performance art truly created? Artists confront not a tangible audience, but an imagined gaze of scrutiny. The “performance for the other” in art often constitutes a dialogue with an “other” woven from reality and fiction. This ‘other’ may be a metaphor for social structures or a projection of the artist’s self-awareness. Whether concretely existing or not, it profoundly intervenes in and shapes the creative process. Artists engage in dialogue with an “invisible other”—be it the silence of society and history or the predicaments of self-perception. The artists in this article use performance art to explore and transcend their own limitations, deconstructing and reconstructing their relationship with the “other.” Whether confronting the silence of the outside world alone or grappling with inner conflict within confined spaces, the creative process itself becomes the answer.

Each performance is not merely a visual spectacle, but an artist’s self-directed quest to discover new points of resonance between themselves and this land. It serves more as a response to the intangible oppression, confusion, and history that have lain dormant for years in Xining. Thus, the true significance of performance art in Xining may lie not in mere presentation for others, but in revealing all relationships—both within the self and beyond. It is a process of seeking deeper existence for every creator within the city’s crevices. Here, artists challenge not only the external gaze through their physical presence, but also the封闭 of self-expression and inner dilemmas. While not creating for the “other,” they are precisely exploring a more profound “other.”

Gao Yuan

July 16, 2025

* This article was originally published in the UP-ON Performance Art Archive column of Issue 8, 2025, of Pictorial Magazine.

Organizer: UP-ON Performance Art Archive

Title Sponsor: Chengdu Shangcheng Design Studio