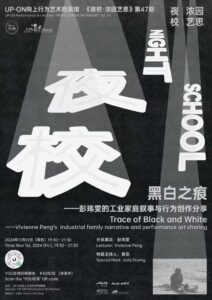

The Research Room section of UP-ON Archives focuses on revitalizing archival materials through theoretical research, seminars, self-publishing, and other initiatives to foster in-depth knowledge production.

The Fleshly Condition and Nomadic Peripheries: Performance Art in Yunnan

——By Luo Fei

Performance art, emerging from early European avant-garde movements in the early 20th century and flourishing in the 1960s and 1970s, has forged its lineage from diverse practices including Futurism, Dadaism, Action Poetry, Happening Art, Event Art, Activism, Fluxus, Situationism, and Guerrilla Theater. It absorbed concepts and methods from diverse fields including dance, music, theater, and social intervention. One could say that the performance art we discuss today is also a collective term for the aforementioned bodily practices, exhibiting qualities—such as improvisation, spontaneity, interactivity, and provocativeness—that other art media typically lack. Performance artists consistently regard the body as a site, exploring its potentialities, its physicality, and its contextualization. This body of concepts and methods, sourced from diverse origins, has continuously formed new contexts and branches throughout its historical evolution. Like an ever-flowing river and its tributaries, it has developed practices relevant to local conditions and needs in different regions. Performance art exhibits distinct tendencies in the West, Asia, China, and even across different regions within China due to varying interpretations of the practice. Therefore, this article adopts “Performance Art in Yunnan” as its observational entry point, briefly reviewing performance art practices that have unfolded in Yunnan since the 1990s. We will observe how, a century after its emergence, performance art is understood, employed, and reinterpreted by artists here today.

The Flesh and Its Contextualization

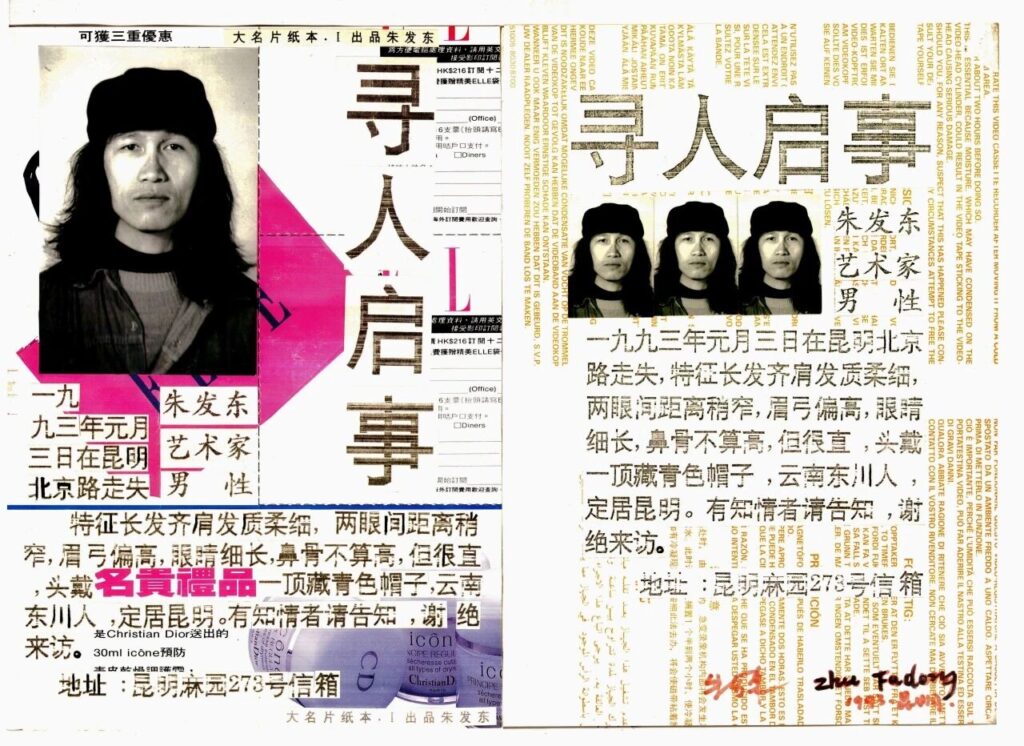

Performance art experienced a surge in China during the 1990s, with numerous young artists choosing this bold medium as their voice. At that time, major art centers and institutional systems were not yet fully established, prompting artists to conduct their practices in public or private spaces—city streets, markets, riverbanks, wilderness, apartments, and beyond. Performance artists of the 1990s placed particular emphasis on public interaction, using this impactful medium to address contemporary issues such as the body, identity, environment, and urbanization. In January 1993, Zhu Fadong drew attention by plastering Kunming’s streets and alleys with “Missing Person” posters bearing his own portrait and physical characteristics. Against the backdrop of massive population flows brought about by rapid urban transformation, the artist positioned himself as one of the many lost souls. Zhu Fading appropriated the “missing person notices” prevalent on the streets at the time to intervene in public space, transforming his personal portrait into a public image to be disseminated and read. It served as both a self-portrait of the artist and a way to render his “self-awareness” and “lostness” into a social misfortune.

Zhu Fadong, “Missing Person Notice” 1993, Kunming

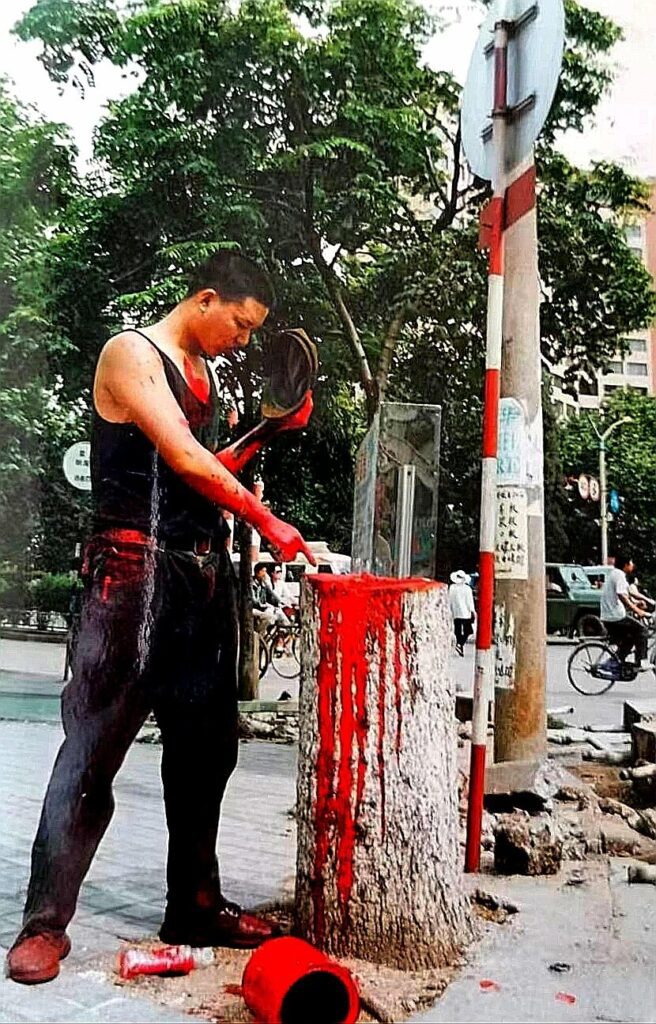

Again against the backdrop of large-scale urban redevelopment, between 1995 and 2000, Tang Jiazheng was implementing his Sacrifice of Species in the Great Belt series in Kunming. He poured red paint over the trunks of massively felled street trees, making them appear as if blood were gushing forth. In Spirit of the Land—Saving Dianchi Lake, he spent nearly every day in Kunming’s Panlong River scooping up the rampant water hyacinth. Tang Jiazheng was among Yunnan’s earliest artists to engage with urban transformation and environmental protection through performance art, garnering extensive coverage in local media at the time.

Tang Jiazheng, Sacrifice of Species in the Great Land 1#, 1995, Kunming

Photo courtesy of Liu Yufang

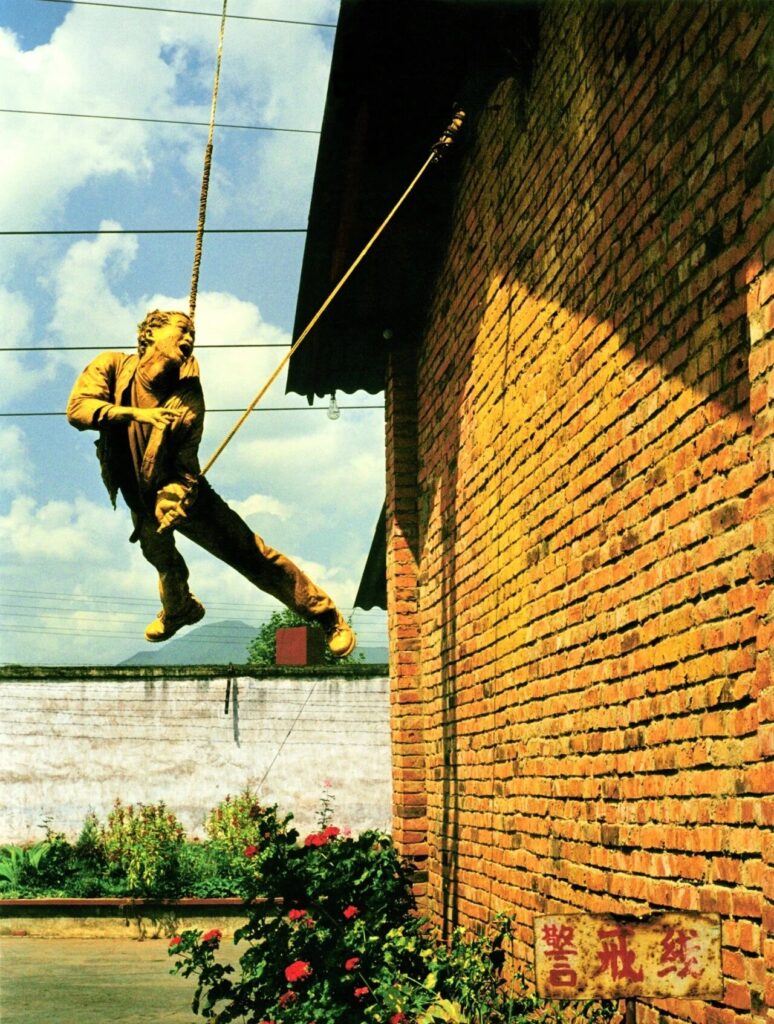

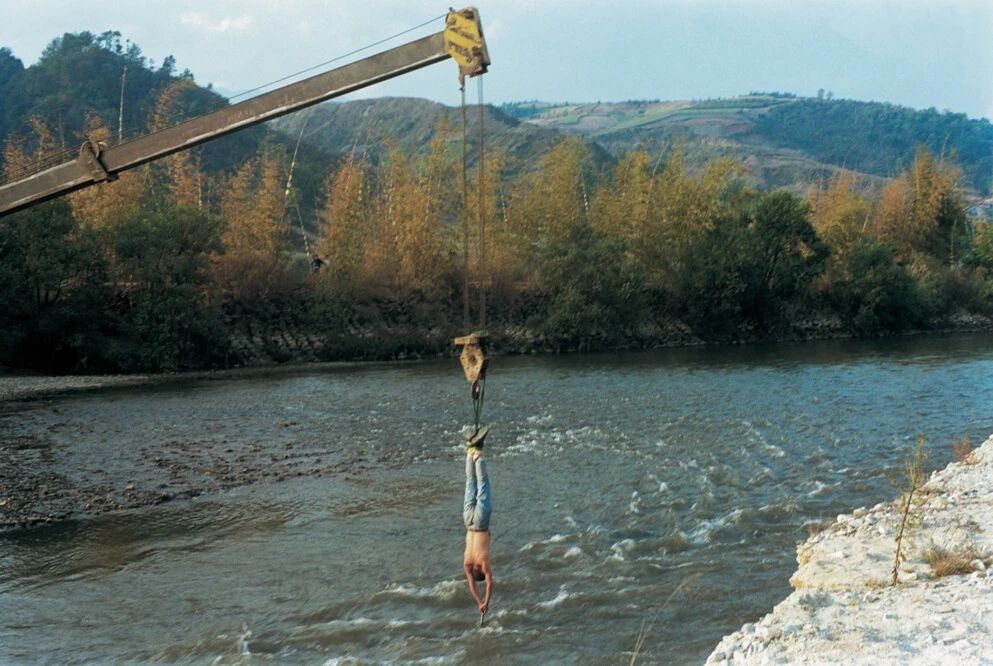

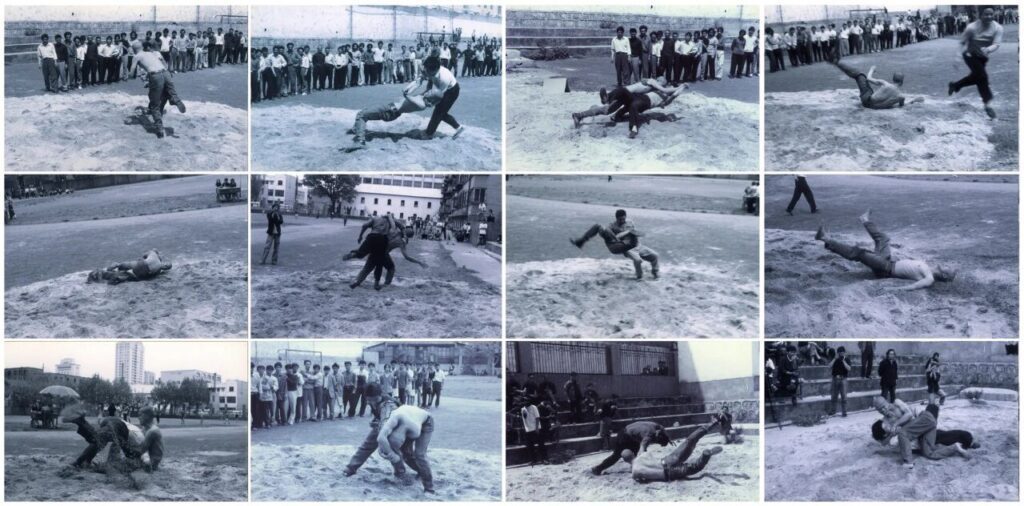

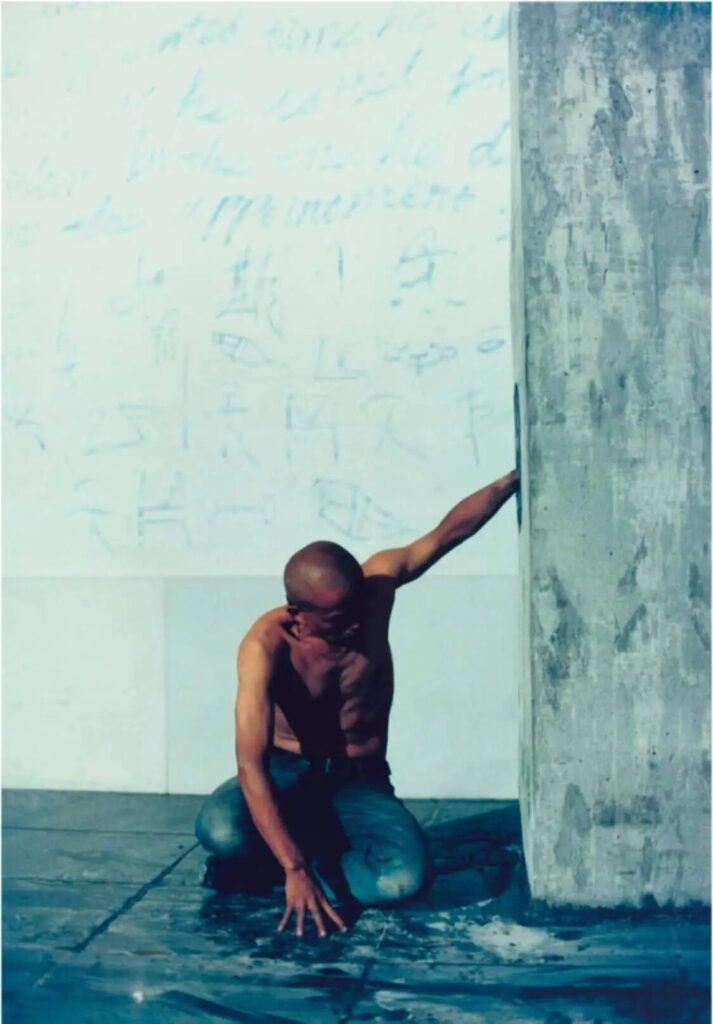

He Yunchang began his series of performance art explorations in the 1990s. In 1993, he staged his first performance piece, “Bankruptcy Plan,” at an exhibition opening at Yunnan Arts Institute. Clutching seven boxes of discarded bonds, he scattered them from the rooftop courtyard while shouting, “Bankrupt! Bankrupt!” In 1998, after reading a local newspaper report about a laid-off worker’s family committing suicide by poisoning due to poverty, He covered his entire body in mud, sat on a chair, and used a disconnected telephone to make “Reserving Tomorrow,” highlighting the distance between the cold present and the unseen future. In 1999, He Yunchang performed his later widely recognized work Golden Sunshine at Kunming Anning Prison. Suspended from the prison’s outer wall, he held a mirror to his chest, reflecting sunlight from the courtyard into the dark, damp prison cells. That same year, in his hometown of Lianghe, he performed “Conversation with Water.” Suspended upside down from a crane arm, he held a long knife whose blade cut his wrist, allowing blood to drip down the blade into the river. In another work, he attempted to move a mountain 835 kilometers from west to east in 30 minutes by pulling it with ropes, harnessing Earth’s rotation to realize the concept of “Moving Mountains.” In 2001, He Yunchang engaged in a 30-minute battle against a high-pressure water cannon in his work Gunman. That same year, in Wrestling 1 and 100, he wrestled 100 people until exhaustion. At the 2003 Lijiang International Work Exhibition Festival, he encased his left hand in a concrete pillar for 24 hours. In this agonizing piece, The Pillar of Faith, he responded to the ancient tale of “Wiseng Clinging to the Pillar.” Through this series of early works created by He Yunchang in Yunnan, we witness the artist’s gradual shift from the socially conscious themes prevalent in the 1990s art scene toward extreme explorations using the body as a medium. He transformed the conceptualist expressions common in 1990s Chinese performance art into visceral, physical confrontations. By fully surrendering his body to environmental challenges, the artist subjected audiences to profound sensory shocks and even ethical dilemmas.

He Yunchang, Golden Sunshine, 1999, Kunming

He Yunchang, “Conversation with Water,” 1999, Lianghe, Yunnan

05 He Yunchang, Wrestling 1 and 100, 2001, Kunming

He Yunchang, “The Pillar of Trust,” 2003, Lijiang, Yunnan

The physical condition of the body has also been a focus for female artists. Since 2000, Sun Guojuan has annually covered her entire body in white sugar, photographing herself in half-length or full-length shots. Through performance photography, she documents the gradual aging of the female form over time. Sun named this lifelong project Forever Sweet, exploring the objectification of the female body under patriarchal gaze and women’s self-identity. In July 2002, the Long March Project arrived at Lugu Lake in Yunnan, where a dialogue unfolded between feminist art pioneer Judy Chicago and Chinese female artists. There, Sun Guojuan executed “Following You” using Mosuo genealogical charts and personal narratives from community members. Lei Yan created the image works “If the Long March Were a Feminist Movement” and “If They Were Women.” Fuliya sealed a text responding to If Women Ruled the World in a glass bottle, threw it into Lugu Lake, retrieved it, and presented it to a Mosuo elder and Chicago. Numerous female artists from other parts of China also engaged in diverse on-site creations—images, screenings, installations, performances, and discussions. Though not strictly performance art, the event constituted a significant dialogue grounded in bodily experience and female identity.

Interacting with the environment through the body was also a common approach among Yunnan artists. Between 2004 and 2008, Wu Yiqiang created performance photography works like Bridges and Dwelling in multiple outdoor settings across Yunnan. He used his body to build physical “bridges” across fractured spaces in the environment or curled into narrow spaces to form a “dwelling”-like filling. In 2009, at the foot of Lijiang’s snow-capped mountains, Liu Lifeng wrapped herself entirely in plants, camouflaging herself as part of the environment while wandering across vast grasslands. During his student years, Xin Wangjun’s street performances in Kunming—Money & Power (2007) and Kunming, I’m Leaving (2008)—garnered widespread media attention. In 2015, he erected several-meter-high pillars on Kunming streets and stood motionless atop them for hours in “Homage.” In 2016, he painted himself green on Shizong’s Mushroom Mountain and exposed himself to the sun for three days in “Nature,” allowing the green paint to fade.

Sun Guojuan, Forever Sweet, 2002, Kunming

The Long March Project at Lugu Lake, Yunnan: Lei Yan, Shen Yu, Fu Liya, volunteers, Judy Chicago, Huang Yin, Sun Guojuan, Liu Hong, et al., 2002.

Artists from the “Long March Project” at Lugu Lake, Yunnan: Su Yabi, Huang Yin, Song Ziping, Wei Shuling (USA), Lei Yan, Sun Guojuan, Zhang Lun, Fu Liya, Shen Yu, Su Ruyi, et al., 2002.

Xin Wangjun, Nature, 2016, Shizong, Yunnan

Here we observe that performance art, as a direct and embodied form of intervention addressing real-world circumstances, has become a preferred mode of expression for numerous Yunnan artists since the 1990s due to its capacity to stimulate public attention and discourse. Although performance art creation may represent only a transitional phase in an artist’s career.

Nomadic Peripheries

The 2005–2006 Jianghu Project represented Yunnan’s most dynamic artistic scene during this period, where numerous performance-based creations emerged within its framework. Organizers integrated folk artists and wandering practitioners into exhibition spaces, blurring boundaries between art and daily life, exhibitions and markets, creators and audiences. Jianghu consistently adopted a nomadic approach—shifting from art spaces to residential neighborhoods, streets to bars, villages to wilderness, and day to night. Unsatisfied with the conventional exhibition spaces of the art elite, Jianghu reactivated entire geographical spaces, forging tight connections with local communities, media, and the public to create a carnival-like atmosphere. This unrestrained live environment provided a new experimental ground for numerous young artists and attracted participation from many international artists.

As one of Jianghu’s curators, He Libin launched extensive performance art projects during this period. In 2005, he staged “Sitting in a Well, Gazing at the Sky” in a bar, isolating himself from the noisy environment with a screen. Inside, he rendered the entire surroundings in ink wash based on external light and music—a work that can be seen as the prototype for his later “Blind Painting” project. In 2010, at the opening of the “Bridge” project at TCG Nordica, He Libin premiered “Shadow.” He pinned his entire black outfit to the wall with thread, casting a massive silhouette under intense lighting. The performance depicted his struggle to break free from his own shadow, marked by the jarring sound of snapping ropes and a palpable visual tension. In 2012, He Libin began composing performance protocols using the Fluxus concept of “event scores,” later evolving this into poetic writing. During this phase, he produced numerous event scores and poetic texts that served as descriptions and self-interpretations of his performance works, revealing the poetic sensibility inherent in his practice. In 2013, He performed Departure in Lijiang, trapping himself within a sealed plastic membrane space where he ran frantically. His movements stirred up ash scattered on the floor, causing suffocation and exhaustion. Against the backdrop of his hometown Lijiang’s landscape viewed through a train window, the performance intensified a profound sense of homesickness and Sisyphean physical futility. In 2014’s “Reconstructing the Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains,” he hung countless black balloons filled with ink on exhibition walls, then systematically punctured them with a whip, allowing the ink to flow down the white surfaces and create an effect reminiscent of freehand landscape painting. In recent years, He Libin has immersed himself in wilderness and ruins in performances like “Dongchuan Narrative” (2011–2019) and “Ruins—Dust” (2023), engaging in dialogue with natural elements such as dust, rocks, rivers, and withered grass… The above works represent only the tip of the iceberg among He Libin’s hundreds of performance moments, yet they reveal the fundamental methods and spiritual essence of his behavioral creations across different phases.

Here we observe He Libin’s shift from conceptual expression to poetic embodiment in his performance art. He integrates performance with daily life, emphasizing the interaction between bodily posture and environmental elements—objects, time, weather, and more. He Libin possesses a keen sensitivity to diverse spatial contexts, roaming different locations for impromptu performances where he channels his emotions through landscapes and objects. He transforms performance into a moment of synchronicity within the growth of all things, while also imbuing the barrenness of reality and his own inner world with poetic resonance.

He Libin, Shadow, 2011, Kunming TCG Nordica Cultural Center

He Libin, Departure, 2013, Lijiang, Yunnan

He Libin, Reconstructing the Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, 2013, Kunming Dazang Art Center

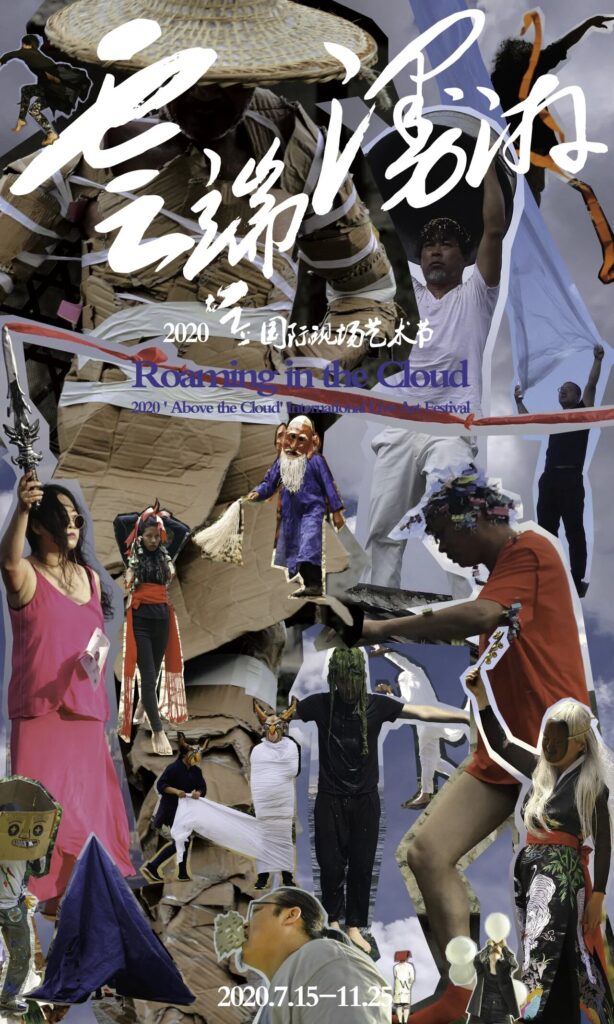

He Libin is not only an artist but also an active curator and key promoter of performance art in Yunnan. In 2009, he launched the “Above the Clouds—International Live Art Festival.” The festival emphasizes participants’ navigation and transitions across diverse spatial environments, geographical conditions, and cultural contexts, inviting them to perform during their travels—with individual and collective performances frequently intertwining.

As one of China’s few dedicated performance art festivals, “Above the Clouds” distinguishes itself through its nomadic approach, unfolding within Yunnan’s unique geography and rich cultural landscape. The festival has invited outstanding performance artists from multiple generations, both internationally and domestically, to Yunnan. Their compelling performances have provided local audiences with opportunities to experience the art form’s unique appeal. Participating artists include, but are not limited to: Monika Günther and Ruedi Schill (Switzerland), Seiji Shimoda (Japan), Chumpon Apisuk (Thailand), Watan Uma (Taiwan, China), Cai Qing, Zhou Bin, and younger generation artists such as Tong Wenmin, Liu Xianglin, and Wang Yanxin. “Above the Clouds” also featured curators and writers from various regions participating as observers, including Lam Hon Kin (Hong Kong, China), Du Xiyun, Xu Qiaosi, Ni Kun, Zhang Haitao, Cui Fuli, Cheng Ai, and local Yunnan observers Luo Fei and Xue Tao. Younger-generation performance artists from Yunnan, including Yang Hui, Liu Hui, Li Zhiyang, Tang Weichen, Liu Ao, Chang Xiong, and Li Yuming, also infuse the festival with vitality. Emphasizing improvisation and nomadic scene transitions, the festival generates an exceptionally large volume of works, providing rich case studies for further discussions on nomadic practices of the body within specific geographical spaces.

2020 “On Clouds—International Live Arts Festival” Poster

The 9th “On Clouds—International Live Art Festival” At Changchong Mountain, Kunming 2019

Monika Günther and Ruedi Schill (Switzerland) Performance at the “On Clouds” Art Festival 2016, Kunming

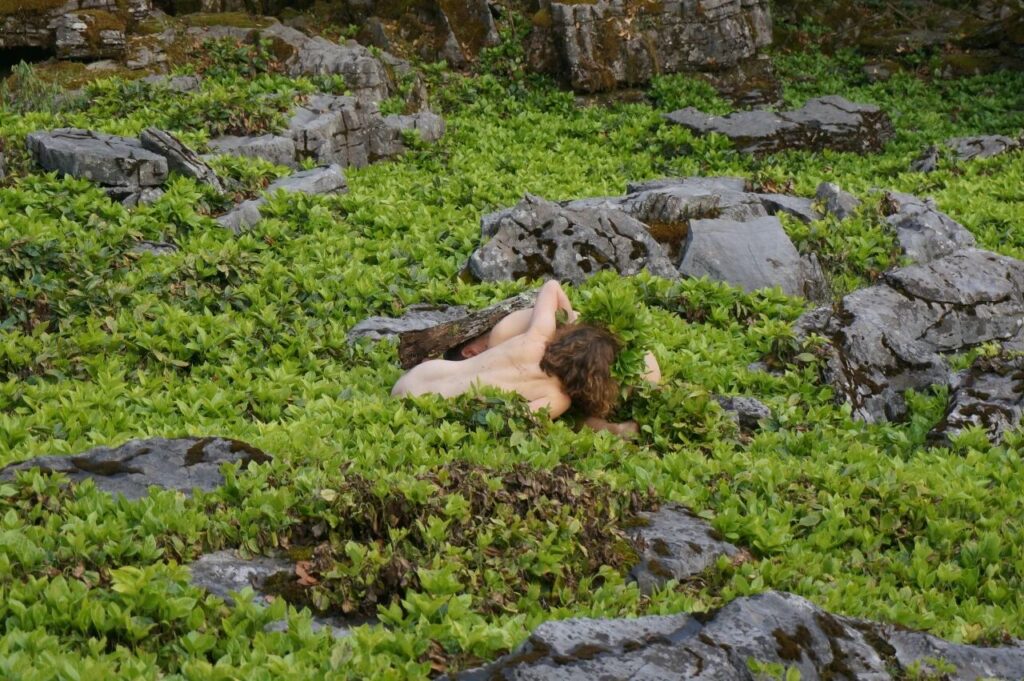

Beatrice Didier (Belgium) and Evamaria Schaller (Germany) in their improvisational performance Approaching Infinity in the Landscape, The 4th “Above the Clouds—International Live Art Festival,” Shizong, Yunnan, 2016

Wadan Uma, Ruins Improvisation, 2019, Kunming Mayuan, Former Site of Yunnan Arts Institute

Chumpon Apisuk (Thailand) Untitled, “Above the Clouds—International Live Art Festival” 2023, Kunming FUN·Art Space

Japanese performance artist Seiji Shimoda (fifth from right) with artists from the “Above the Clouds—International Performance Art Festival” 2017, Lijiang Studio

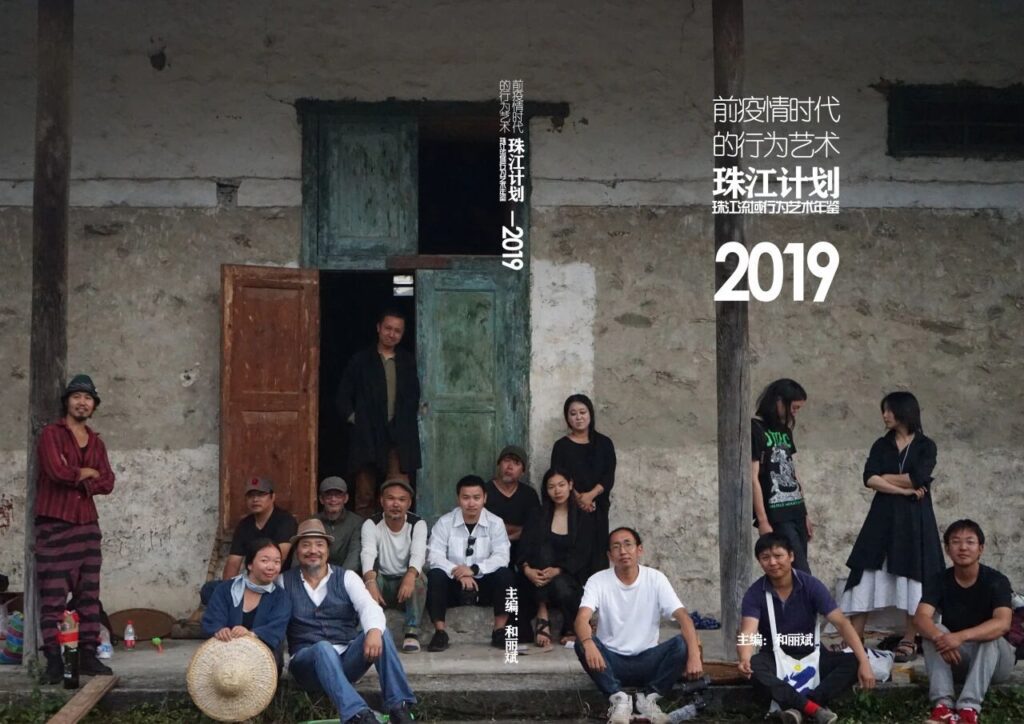

Beyond organizing and planning art festivals, He Libin co-founded the Pearl River Project in 2017 with Guangxi-based artist Yin Tianshi and Shenzhen-based artist Liu Xianglin. This initiative focuses on compiling documentation of performance art within the Pearl River Basin region. Here we observe that performance artists represent one of the few contemporary artist groups that consistently maintain self-organization and mutual connections, actively collaborating both domestically and globally.

Simultaneously, He Libin has championed local performance art education. Initial efforts began in 2014 when Norwegian conceptual and performance art pioneer Hilmar Fredriksen was invited to lead a workshop at the Fine Arts College of Yunnan Arts University. This marked the first public performance art course at a Yunnan university, led by Fredriksen with assistance from He Libin and Luo Fei. Following this, He Libin and Luo Fei conducted two additional performance art workshops at Yunnan Arts University, after which He Libin continued teaching independently. In 2016, He Libin began collaborating with various local art spaces to offer personal performance art workshops. During this period, He Libin hosted visiting performance artists from other regions through “performance gatherings,” facilitating exchanges and artistic collaboration through outings and impromptu performances. In 2017, he initiated the “Kunming Performance Art Week,” bringing together activities such as performance gatherings, performance theater, lectures, and other performance art-related events for a concentrated presentation.

Cover of the 2019 Pearl River Project Performance Art Documentation

The First Performance Art Workshop Held at Yunnan Arts University Norwegian performance artist Herma Fredericksen led students in meditation exercises March 6–8, 2014

Behavioral Friendship: Mimicry Held at the Wangtian Tree Scenic Area in Xishuangbanna Tropical Rainforest Park, artists employed performance art to depict the extraordinary phenomenon of mimicry within the tropical rainforest, expressing the harmonious symbiosis between humanity and nature. 2019

“On the Clouds” Art Festival: Collective Improvisation Performance “Variations” Kunming, 2015

Similarly tied to travel, yet distinct from performative practices emphasizing bodily expression, embodied practices centered on knowledge production reveal another dimension. Since 2015, Cheng Xinhao has transformed his research on Yunnan’s geographical spaces and historical strata into embodied treks and adventures. By reopening local imaginations through the travel experiences of historical figures like Xu Xiake, he has allowed Yunnan’s modernity narratives to resurface through explorations of railways, postal roads, and transportation networks. Though Cheng does not identify as a conventional performance artist, his long-term personal projects—marked by genuine physical commitment and the intensity of his actions—reconnect the body with place.

Cheng Xinhao, “To the Ocean” Stills (2019) Single-channel video (color, sound), 49 min 56 sec Image courtesy of the artist and Tabula Rasa Gallery

Conclusion

After briefly reviewing Yunnan’s performance art practices since the 1990s, we observe that within just a few decades, both the methods and concepts of performance art have undergone profound transformations. Pioneers like Zhu Fadong and He Yunchang laid the groundwork, while He Libin actively propels the field today. As one of China’s key performance art scenes, Yunnan has developed its own distinct trajectory and ecological characteristics.

Unlike the earlier generation of performance artists who emphasized independent creation, crafting strong formal sensations and sensory shocks, recent years in Yunnan have seen performance art practices increasingly anchored in collective events like the “In the Clouds” Art Festival and “Performance Gatherings.” A new generation of creators integrates physical language exploration with outings, everyday life situations, and the aesthetics of living, crafting moments of carefree performance. These shared performances, mutual observation, and collective exchanges form a daily practice within a nomadic state on the periphery. In regions lacking artistic resources, this approach serves as a viable strategy for sustaining artistic production. Here, performance art has shifted from the radical, confrontational body concepts of early avant-garde movements toward site-specific explorations that integrate with the environment.

So, how do Yunnan’s artist communities perceive and respond to the rapidly changing universal concerns of our time through their nomadic journey? Can they discover their own tools within this nomadic existence? As a region rich in natural resources and possessing a unique geographical environment, can Yunnan offer an alternative path of practice distinct from the central systems? These questions may find answers in subsequent observations.

—Luo Fei

May 4, 2025

Originally published in the UP-ON Performance Art Archive column of Issue 6, 2025, of Pictorial Magazine.

Organizer: UP-ON Performance Art Archive

Title Sponsor: Chengdu Shangcheng Design Studio