——The Practice of Social, Non-Human and Caring

by Guicheng Liu

Introduction

The 13th UP-ON International Live Art Festival officially opened on October 18, 2025. In fact, even before the opening, the public had already encountered the artists and their practices through various formats, including artist workshops and the “Artist Marathon.” Yet regardless of how one approaches performance art, one must ultimately return to the live moment.

In performance art, the transmission of knowledge—whether through artists’ own explanations of their work or through scholars’ written accounts—can only ever touch the outer edge of experience. As an observer, I am keenly aware that any description of the 现场 (the live site) can never truly reproduce that instantaneous, embodied, phenomenological experience. What writing can undertake is only an interpretive form of knowledge generated through individual perception—art knowledge as practice.

It is precisely from this irreparable absence that we are led to the complex relationship between performance art, or more neutrally and inclusively, live art, and artistic archives. While these relationships are not the central concern of this article, they nonetheless constitute a longstanding core issue within performance studies and art history.

In a certain sense, this text itself may also be regarded as a form of “artistic archive.” It records the occurrence of the 13th UP-ON International Live Art Festival and may, at some future moment, be recalled in the form of “ruin memory.” When the performances have ended, and all material remnants of the site have turned into ruins, writing also persists as part of that ruin. It calls forth the history of performance while simultaneously pointing toward possible futures of performance art. In a gestural manner, the words within the archive continuously reshape history, allowing performance to extend its life through writing.

Moreover, as this was my first time participating in the UP-ON International Live Art Festival, my perspective is primarily field-based and site-oriented. The historical dimensions addressed here derive more from the artists’ creative trajectories than from the institutional history of the festival itself. This means that my narrative logic largely follows a path of performance – scene description – analytical interpretation, thereby offering a perspective that is at once personal and broadly resonant.

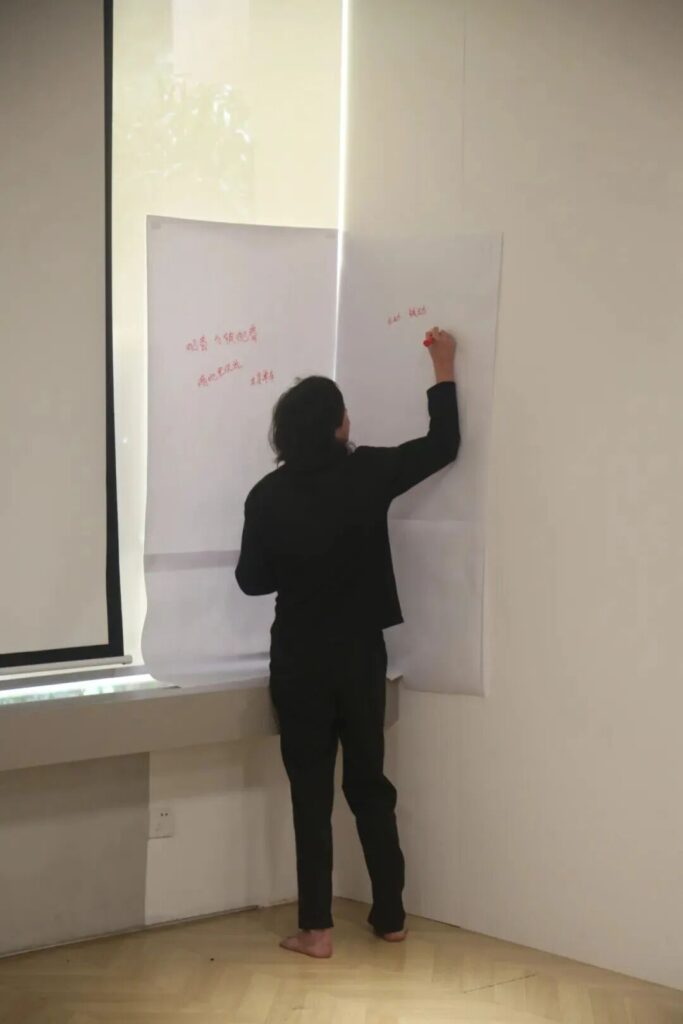

HU Yingchao (CHINA, Shanghai)

Title: A Cornered Artist

Duration: 30 minutes

Difference and Totality: The Live Art Festival as Dramaturgy

Returning to the notion of the “festival,” we encounter an inherent paradox. On the one hand, a festival brings together different artists and attempts to subsume them under a particular formal framework; on the other, singularity is precisely what artists consciously or unconsciously seek to pursue. This is especially true for performance artists, who come from diverse backgrounds. Among the participants of this live art festival are artists originally trained in performance art, others who began with visual practices such as painting, and still others whose work extends from broader performance fields—such as dance or music—into action-based practices. In fact, it isn’t easy to integrate them under a single thematic rubric.

This plurality is not only a defining feature of the festival but also a challenge faced by the festival team. Formally, their role may be likened to that of “curators”; yet from the perspective of performance generation, I am more inclined to understand their work as dramaturgy. As art curator Kathy Halbreich has noted, “the curator is also becoming analogous to a dramaturg, unpacking the context and the meaning, helping the cast move forward with that understanding, enriching the sense of the performance.” In this sense, festival organizers are not merely arranging performance sequences or spatial layouts; they are also generating latent relationships among works, allowing actions that appear independent to form a hidden structural resonance on site.

Li Yanzeng(CHINA, Bejing)

Title: 2/4/3

Duration: 35 minutes

Regardless of whether the UP-ON festival team consciously choreographed the artists’ performances, these works indeed formed an integrated field of perception through the interweaving of time and space—a “live logic” that exceeds thematic unification and is constituted through the coexistence of differences. This logic is neither predetermined nor retrospectively summarized; rather, it is continuously produced through the collisions among performances and the audience’s experience of being present.

As the opening performance of this edition of the festival, Shanghai-based performance artist Hu Yingchao presented A Cornered Artist. At the beginning of the performance, he stood with his back to the audience, his body pressed against a corner of the wall, murmuring to himself while continuously writing keywords on sheets of white paper posted in the corner. The overall form resembled a lecture performance, yet its narrative was deliberately interrupted and distorted, producing a self-interrogative live structure. Through these mutterings, Hu repeatedly questioned the boundaries of performance art: What constitutes an “action”? What constitutes “art”? While the co-presence of audience and performer forms a core condition of performance art, Hu adopted a stance of turning away that refused both looking and being looked at. However, this refusal itself was transformed into a performative strategy. While concealing himself, he simultaneously simulated the state of being watched, even adopting the audience’s perspective to cast doubt upon his own actions: “Is this really performance art?” This reflexive staging drew the audience into the philosophical terrain of artistic definition, echoing George Dickie’s “institutional definition” of art as an artifact of a kind created to be presented to an artworld public. Within this context, Hu posed a subtle irony: if the same performance were carried out by Marina Abramović or another internationally renowned artist, would its status as art be recognized differently?

This irony points to the “politics of identity” within the field of performance art, where artists are constantly categorized as “performance artists,” “installation artists,” or “video artists”—classifications that ultimately obscure the generative nature of action and the agency of the body. In the latter part of the performance, Hu emerged from his murmured monologue in the corner and began to engage his body in a more open manner, revealing his background as a dancer. As the body entered a rhythmic mode of use, the performance gradually slipped into the vocabulary of dance, compelling the audience to reconsider the boundary between “dance” and “performance art.” It was precisely within this continual cycle of self-definition and negation that the performance became a form of knowledge practice. Rather than offering answers, Hu repeatedly posed questions through action, casting the problem of “what constitutes performance art” back to those present, and rendering spectatorship itself a mode of thinking.

As the first work of the festival, it did not open the program by chance. Rather, through a gestural mode of action, it established an intellectual point of departure for the entire event. In this sense, every performance that followed, to varying degrees, extended or responded to the questions raised by Hu Yingchao: how performance art is to be defined, viewed, and institutionalized in a contemporary context. By employing the bodily metaphor of being “forced into a corner,” Hu exposed the tensions between the artist and institutions, audiences, and media. At the same time, the work symbolically interrogated the festival itself: when “liveness” becomes something curated, archived, and written about, how can performance art recover its generative force?

Similarly, at the opening of the second day at A4 Art Museum, sound artist Li Yanzeng constructed an “audibilized” field for the audience. By adjusting two synthesizers positioned at opposite ends of a long table, he set sound in constant circulation through the space—oscillating, reverberating, and lingering, from low-frequency drones to high-frequency pulses. Gradually, this flow of sound drew the audience into a perceptual experience that resisted verbal articulation. What emerged was a form of pure “phenomenological presence”: the audience was no longer the subject that listens, but rather the medium through which sound appeared. Detached from semantic meaning, sound operated materially—through vibrations in the air, reflections in space, and resonances in the body—acting directly upon perception itself and allowing auditory experience to exceed semantic comprehension. Li Yanzeng’s work foregrounded the influence of pure numerical and geometric logics on music, seeking as much as possible to strip away human elements and meaning grounded in human intentionality.

From this perspective, Li’s sound performance provided a sensory framework for the subsequent performance art presentations: the audience was trained to feel rather than to interpret. The “materiality” of sound here became a gateway to experience, fusing the temporality and spatiality of perception. The day also concluded with Li Yanzeng’s performance. Moving through the space with a synthesizer in hand, he allowed sound to circulate and leave traces among walls, floors, and bodies. At this point, sound was no longer the object of performance but became an “experienced atmosphere.” As the electronic sounds gradually faded, the audience became newly aware of the silence of the space, and the second day of performances found closure and resonance within this quietude. The opening and the ending thus formed a perceptual circle: sound functioned both as the point of departure of experience and as its afterglow.

At the level of dramaturgical construction, the festival can be said—intentionally or not—to have presented itself as a coherent whole. Its unity did not rest solely on a theme or curatorial discourse, but was provisionally woven through synchronic resonances and cycles of perception among the works. The logic of the festival resided in the correspondences, ruptures, and deferrals between performances. Each work, through its own specificity, participated in the generation of the whole, rendering the “festival” a dynamic thinking apparatus. Here, meaning was not predetermined, but produced in the intersections of action and perception.

Ritual Performance: Ruins as a Site of Spatialized Performance

On the first day of the festival, the abandoned swimming pool of the Jinyue Children’s Art Museum became a crucial stage for the performance artists. Three artists—Liu Hui from Kunming, Carlos Llavat from Spain, and the Swiss artist Luc Häfliger—each chose this site, yet engaged with it from markedly different directions. Once a space of leisure and circulation, the abandoned pool has now become a container for time, memory, and the body. It is precisely within this condition of “abandoned modernity” that a resonance emerges between site and body, rendering site-specific performance a metaphorical articulation of contemporary experience.

Liu Hui’s work Track comes closest to this sense of embodied realism. He installed two facing mirrors and a bicycle inside the pool. The mirrors reflect not only the image of the body, but also a self that is fragmented, repeatedly affirmed, and continually dissolved within the process of modernization. Moving back and forth between the mirrors, the artist persistently cut his clothing and shaved his hair, while cycling and falling in repeated cycles that subjected his body to an almost punitive rhythm. Bodily injury and the ruinous space of the pool overlap, forming a traumatic metaphor for the individual’s loss of direction and belonging amid urbanization.

Carlos Llavat’s Today I’m Very Sad to Tell You activated personal life experience through a more explicitly ritualized approach. The empty swimming pool was transformed—together with the Chengdu-based local band Yuan Wen Qi Sheng—into an altar infused with the sonic qualities of southwest Chinese ethnic traditions. Blood, rice paper, and rhythmic drumming intertwined to create a shamanistic ritual scene. With blood covering his head and sheets of rice paper bearing the word “time” in his hands, Carlos combined bullfighting gestures with the stillness of a “human clock hand,” reconstructing a “ritual of time” through a cross-cultural vocabulary. He appeared to be wrestling both with time and with cultural identity. When Spanish bullfighting music was juxtaposed with Chinese ethnic music, a reverse colonial echo emerged within the space: a foreign body articulated in displaced ritual languages, giving form to emotions that resist speech.

LIU Hui (CHINA, Kunming)

Title: Track

Duration: 40 minutes

Carlos Llavata (SPAIN)

Title: Today, I’m Very Sad to Tell You

Duration: 30 minutes

Luc Häfliger’s Love Sick Heretics most directly transformed the swimming pool into a religious theatre. Drawing on the resonance of the dome and the collision between sound fields and noise, he generated an atmosphere that was at once sacred and profaned. The work oscillated between prayer and cacophony, repeatedly pulled back and forth between ritual solemnity and disorderly turbulence. At its core was the theme of a “love that requires no sacred mediation.” When roses were distributed, affect was rendered tangible as a sacred overflow rather than as something conveyed through an intermediary. This gesture functioned both as a challenge to the established order and as an exposure of the fragility of human emotion. Luc’s performance entered into an intertextual relationship with Joseph Baan’s work on the second day of the festival, Out of Joint (The Schreber Case). Joseph likewise chose an abandoned building near the A4 Art Museum, where exposed reinforced concrete and fire hydrants evoked a scene of apocalyptic judgment. As the title suggests, both Joseph and Luc employed disoriented gendered costuming to stage a canonical case from the history of psychoanalysis, translating Schreber’s gender dislocation and sacred delusions, as discussed in Freud’s writings, into performative actions. Anus and mouth—representing different phases of libidinal development—were filled with foreign objects, an image that implied an extreme visualization of sexual violence.

Taken together, these works mobilized semi-ruinous, site-specific spaces in which the body became a witness to social and cultural ruptures, while the site itself responded to individual pain and desire through its historical fissures. Here, the site was no longer merely a backdrop for performance, but a co-constitutive mechanism in the production of meaning alongside the body.

Luc Häfliger (SWITZERLAND)

Title: Love Sick Heretics

Duration: 30 minutes

Joseph Baan (SWITZERLAND & the NETHERLANDS)

Title: Out of Joint (in process)

Duration: 40 minutes

Identity, Society, and Life and Death: Cross-Generational Practices in Chinese and International Performance Art

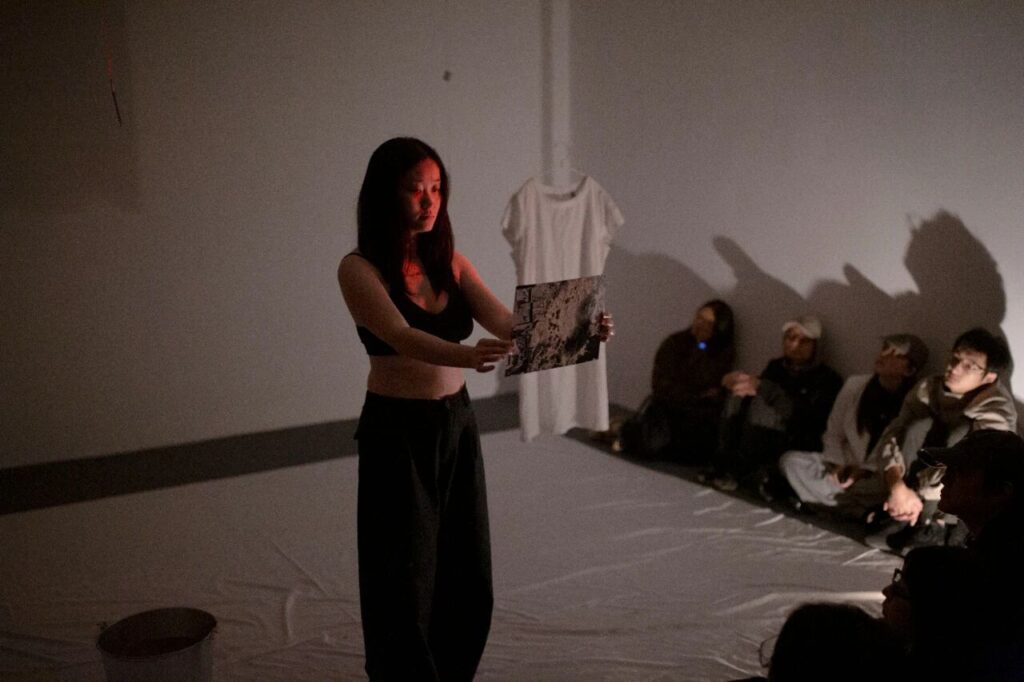

The works of several emerging artists—Li Duo’s Volcano Fitting Room, Yu Yuling’s The Extinction of 21, Peng Jing’s Strings, and Wei Mingyi’s Presence in Dissolution—collectively reveal how contemporary young artists take the body as a point of departure to explore the tension between individual identity and socio-political belonging. Li Duo’s Volcano Fitting Room exposes the condition of being watched within structures of social power through mechanisms of surveillance and voyeurism embedded in a confined space. As the artist repeatedly strips the body of various personal and social objects, the “self” is dismantled and reassembled, revealing its fragility and fluidity. Yu Yuling’s The Extinction of 21, by contrast, stages the gradual melting of colored ice blocks that seep into white garments, visualizing the process by which a pure identity is permeated by time, memory, and social experience; the diffusion of color becomes a metaphor for both assimilation and regeneration of the self. Peng Jing’s Strings further materializes this tension by constructing fragile, interdependent connections between bodies through threads, rendering “relations” no longer a psychological metaphor but an embodied and dynamic network. In comparison, Wei Mingyi intertwines the everyday with the socio-political to reveal the interpenetration of the private and the public. On the one hand, washing gestures are metaphorized to revisit familial memory, bringing latent emotions and power relations within family structures into the exhibition space. On the other hand, the act of cleaning references images of war-torn cities drawn from satellite maps—including Gaza, Syria, and Kyiv—which exposes the individual’s sense of powerlessness in the face of large-scale political trauma. Across these performances, young artists continually locate and affirm their positions within diverse social spaces, with the body serving as the most immediate medium of this process.

LI Duo (CHINA, Hangzhou)

Title: Volcano Fitting Room

Duration: 10 minutes

Yu Yuling (CHINA, Shenzhen)

Title: The Extinction of 21

Duration: 30 minutes

PANG Jing (CHINA, Hong Kong)

Title: Strings

Duration: 45 minutes

Wei Mingyi (CHINA, Chengdu)

Title: Presence in Dissolution

Duration: 30 minutes

Ding Ling’s Farewell Practice I, the only durational performance in this year’s festival, constructs an allegory of “expenditure” and “existence” through sustained bodily movement pushed to its limits. Dressed in pure white, the artist steps onto a treadmill and confronts the passage of time through hours of walking and mechanical repetition. As exhaustion accumulates and the body approaches depletion, it becomes a figure for the gradual dissipation of life itself. This process not only stages a struggle between the individual and time, machinery, and fate, but also transforms into a phenomenological experience: as viewers witness the body’s progressive disintegration, they encounter the threshold between life and death. The release of a sky lantern at the end of the performance responds to the preceding corporeal struggle with lightness and emptiness, symbolizing a form of transcendence akin to “affirmative nihilism.” In this sense, Farewell Practice I is not merely a personalized allegory of life and death, but a declaration of the artist’s courage in confronting ultimate questions through the body.

DING Ling (CHINA, Shanghai & Luoyang)

Title: Farewell Practice I

Duration: 3 hours

Also engaging with the theme of death is Dong Nu’s work Every Inch of Earth Bears with the Dead. In the performance, the artist repeatedly throws garments into the air, allowing them to fall onto the ground, and then traces their contours on the earth with white latex paint. Through this repeated gesture of tossing and falling, the garments become both substitutes for the body and residues of memory and death—they hover, collapse, and are buried, symbolizing the cyclical movement of life between disappearance and return. Once fixed onto the soil, these garments resemble “the shapes of the dead,” materially evoking the presence of those who have passed away yet remain unforgotten. “Land” here is no longer a mere background or support, but a medium that absorbs, records, and bears both the material and spiritual dimensions of death. Resonating with Ding Ling’s Farewell Practice, Every Inch of Earth Bears with the Dead similarly approaches the boundary of death through bodily practice. Yet while Ding Ling reveals the passage of life through the logic of “exhaustive movement,” Dong Nu allows vanished lives to endure through “static imprints.”

Dong Nu (CHINA, Xining)

Title: Every Inch of the Land Is Filled with the Spirits of the Dead

Duration: 90 minutes

These concerns are not limited to Chinese performance artists. Polish performance artist Dariusz Fodczuk presents the dynamic processes of order and chaos, connection and rupture in familial and social relationships through an approach that closely resembles dramaturgy. The Concealed Contents unfolds through what might be called “material metaphors of relationships.” In the first act, the artist repeatedly places ceramic bowls into the hands of two performers; as balance is lost, the bowls fall and shatter. This recurring action renders visible the delicate equilibrium and fragility inherent in human relationships. The second act shifts to another space, where the artist repeatedly covers words written in white on the wall with layers of white paint. This “seemingly reparative erasure” gradually causes the words to disappear, exposing the inefficacy and futility of communication: language is simultaneously obscured and emphasized, while efforts at communication intertwine with misunderstanding. In the third act, the performance escalates into a more intense bodily state. The artist forcefully pulls at a fragile installation made of everyday objects; ceramic bowls scatter across the floor as he steps barefoot onto the shards, eventually collapsing to the ground and writhing as blood slowly spreads. Here, the disorder of relationships is pushed toward a dramatic climax: the body becomes the medium of conflict, and pain marks the limit of communication. Finally, the artist arranges three carpets neatly on the ground, as if imposing a surface-level sense of “order” or “repair” upon the preceding chaos. Yet this calm appears more illusory than resolved. At the end of each act, the artist asks audience members to take instant photographs of him. As the Polaroid prints develop from blank white into visible images, they symbolize the generation, appearance, and disappearance of relationships. Taken together, these theatrical fragments form an allegory of what might be called the “development process of interpersonal relations”: a cycle in which we continually attempt to sustain, mend, and reconstruct connections, only to repeat fragmentation while exposing our own finitude.

Dariusz Fodczuk (POLAND)

Title: THE CONCEALED CONTENTS

Duration: 30 minutes

The Dutch performance art pioneer Peter Baren continued his long-standing engagement with themes of “life” and “death,” reappropriating the performative vocabulary he has developed over the years. His work at the festival, THE GIFT [HIGHER GOALS], forms part of his series Blind Date With The History Of Mankind. In the performance, Baren assumes the role of a “demonic” guide, accompanied by imagery of skulls—an embodiment that gestures toward the shadow of death and evokes the indelible sense of original sin in human history. The artist employs boomerangs as a medium, inscribing them with words such as “earthling,” “spirit,” “meatjoy,” and “crossfire,” as well as a fifth boomerang marked with the Chinese character for “无”(Wu)and the English word “NOTHING” on its reverse. These inscriptions, drawn from his Ark series, constitute a sustained dialectical reflection on the human condition: the tension between body and spirit, the entanglement of desire and violence, and the confrontation between the earthly and the spiritual. The boomerang’s cyclical trajectory metaphorically enacts the return of life and the recurrence of death. During the performance, Baren places several handkerchiefs inscribed with the word “hope” in a circular formation on the ground. He then lays down a single smeared white shirt, an action of particular significance in the Chengdu context. After placing the shirt in front of his body as an act of sensing the dead, Baren covers it with his own body, enacting a gesture of connection with the dead. These materials function both as remnants of memory and as accumulations of performative energy, bearing traces of bodily presence and serving as tangible witnesses to the residue of life. In the final gesture, Baren places one ear to the ground, directing the tension of the performance toward a silent, meditative return.

Peter Baren (the NETHERLANDS)

Title: THE GIFT [HIGHER GOALS]

Duration: 40 minutes

When the focus shifts from philosophical questions of life and death to the more socially grounded realities of war and mortality, the intrinsic social and political logic of performance art is revisited by several artists. In Deej’s Secret Distortion, this sociality is rendered through an intensely intimate framework. The work extends the spatial design of his earlier piece, Digging up Nothing in Kiltalown: audiences enter the backseat of a black van in groups of five, where screens display each artist narrating the pivotal events of their lives. The van functions both as a mobile space and as a vessel for marginal social experiences; spectators are compelled to inhabit this semi-enclosed environment, breathing alongside others’ pain, shame, and memory. The visual motifs in the van, drawn from street sex work, reflect the performers’ appearance, exposing the fragile boundaries between survival and visibility. In this context, Deej constructs a “collective confessional space,” where individual stories are refracted into collective memory, and private experiences become testimonies to societal repression. Audience presence is not mere observation but a form of involuntary empathic participation—bodies, images, and personal and collective experiences intertwine within the van’s confined space, revisiting social wounds.

Deej Fabyc (AUSTRALIA & the UNITED KINGDOM)

Title: Secret Distortion

Duration: 40 minutes

Vichukorn Tangpaiboon (THAILAND)

Title: SUE in China

Duration: 30 minutes

This social interrogation is further extended by Thai artist Vichukorn Tangpaiboon in his performance SUE in China, which navigates the intersection of religion and politics. Through ascetic-like ritual practices, he explores justice, faith, and the purification of the soul. The scattering of salt serves as both a bodily cleansing and a summons to social awareness. The use of dry ice, bells, and a balance constructs metaphors of coldness, divine revelation, and justice, weaving a spiritual predicament. As he shouts, “Where’s justice, blind, I can’t hear,” the body becomes the sole speaking instrument, oscillating between unheard justice and suppressed faith. In the final gesture, he writes on the wall with cement: “performance is here, no politics,” a pointedly ironic statement that reveals the inseparability of art and politics.

The performances of both Chinese and international artists converge on a central proposition: how contemporary performance art reconsiders the relationship between “life” and “society.” From individual exhaustion and the rupture of relationships to the call of the spiritual and the silencing of justice, performance becomes an alternative mode of perceiving reality, thereby revealing the distinctiveness of performance art in exploring this complex web of relations.

Reconfiguring Body, Perception, and Relations: Cross-Species and Non-Human Performance

Several artists at this year’s festival engaged with non-human themes, resonating with broader cultural and scholarly interests in the “posthuman turn” and the “ontological turn,” which consider objects, technology, plants, and their interrelations with humans. The Japanese performance artist Yoshiya Yoshimitsu’s work Clip Piece adopts a distinctly parodic stance—what the artist calls a Neta approach—to reference a highly symbolic moment in the history of performance art: Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964). Neta implies a comedic or playful attitude. Unlike Ono, who positioned her own body as the object to be watched and cut, Yoshimitsu substitutes this “passive body” with a doll. Audiences are invited to gather around the doll and freely cut its clothing, rearrange, or sew the fabric. Compared to the restraint and moral hesitation exhibited when interacting with a live human body, spectators’ actions toward the doll are more casual and playful, reflecting Yoshimitsu’s understanding of Neta. This substitution is not merely a displacement of violence but prompts a reconsideration of human–object relations. The doll, as a surrogate body, redirects human perception and ethical projection onto a non-living entity, revealing the hierarchical and dependent nature of human–object relations within a performative context. In the act of cutting and reshaping the doll, audiences inadvertently participate in an ethical experiment concerning violence and care, simulation and reality. Yoshimitsu concludes the performance with a song resembling a lament; although improvised, it conveys the artist’s experiential engagement with the doll’s status. Through this subtle shift, Clip Piece simultaneously resonates with the performance art tradition of “bodily politics” and redefines relational structures in performance through the mediation of objects. Here, the “liveness” of performance is partially displaced into a form of “quasi-presence,” prompting viewers to oscillate between the playful Neta and the more serious, theoretical Beta frameworks.

Yoshiya Yoshimitsu (JAPAN)

Title: Clip Piece

Duration:45 minutes

Austrian performance artist Lisa Hinterreithner’s work Garden Sensation redefines the perceptual boundaries of performance art through a posthuman “plant performance.” Spectators do not enter the space as human-centered viewers; rather, they move through the environment as “bodies becoming-plant.” The entire gallery is transformed into a “symbolic garden,” where simple line-drawn colorful plants and a soundscape simulating insects and birds create a multispecies perceptual system. Audience members lie on petal-shaped cushions and receive watering and pinecones from the artist. This act of care becomes a cross-species ethical gesture: humans are no longer the subjects caring plants but are “plantified” through a performative reciprocity. Hinterreithner further invites spectators to touch and decorate the plants using wood, branches, water bags, soil, and yarn, simulating the plant’s openness to its environment. The audience’s bodies extend the plants, and perception becomes a form of ecological resonance. At the performance’s conclusion, all spectators collapse near the petals, emitting the buzz of bees, producing a chorus composed of humans, plants, insects, and inanimate materials. In this sense, Garden Sensation is not merely a work about plants; it enacts a “plant-thinking” performance, transforming the event into a site of multispecies perception and deconstructing the human sensorium into a shared ecological apparatus.

Lisa Hinterreithner (AUSTRIA)

Title: Gardening Sensations

Duration: 45minutes

In Liu Zheli’s World Clock, the artist repeatedly asks ChatGPT, in varying tones and emotions, “What time is it there now?” The AI responds with standardized time and continually questions why the artist asks. Over a fifteen-minute loop, this brief interaction evolves into a performance about the “impossibility of communication.” Time, an abstract and universal dimension, is reframed as a site of rupture between human and machine: the AI’s “now” is precise yet hollow, its “here and now” nonexistent, yet constantly produced through the logic of language. This repeated questioning becomes a reflection on modern temporal experience. Each inquiry invokes “world time,” but the feedback is cold, algorithmic, and devoid of emotion—a detached synchronization. The failure of this “cross-boundary dialogue” reveals the virtuality of communication in the digital era: we interact endlessly with algorithms, yet are never truly “responded to.”

LIU Zheli (CHINA, Ulanhot)

Title:World Clock

Duration: 15 minutes

These works collectively demonstrate how contemporary performance art continuously pushes beyond anthropocentric boundaries: the body is no longer merely a carrier of selfhood or social identity, but becomes a medium for dialogue with objects, plants, technologies, and ecosystems; perception is no longer confined to human sight and hearing, but generates new experiential fields through diverse materials, environments, and technologies; and relationships extend beyond tensions between individuals to interactions that span species, media, and temporal-spatial dimensions.

Perception and Care in Performance: Connection and Repair in Art

“Care” emerged as a tender and deliberate choice among artists in this festival, especially in the face of an unpredictable and chaotic world. The question of how performance can carry a motivating, forward-moving force became a central mission for these artists. Irish performance artist Frances Mezzetti, in Heart Speak, constructs an emotional narrative from “self-purification” to “connection with the world” through a series of embodied gestures—wrapping, kneeling, cleansing, wiping, giving birth, and praying. She uses a white cloth as the medium of emotion and language: the “heart words” inscribed on the fabric symbolize both the externalization of personal feelings and the materialization and sharing of inner experience. When she ties strips of the cloth to plants on either side of a bridge, individual spiritual experience expands into a caring gesture that traverses both nature and society. The cloth becomes a tangible link between people and the environment, between self and others. The performance is imbued with metaphors of religious ritual and female bodily politics; washing the face, giving birth, and praying signify not only life cycles and redemption but also respond to contemporary social alienation through the continuity of “body—nature—language.” By transforming ritual into action, Mezzetti makes “care” a bodily practice—generated through repetition and labor, and in the opening of personal experience, it mends the fractures between people and the world.

Frances Mezzetti (IRELAND)

Title: Heart Speak

Duration: 30 minutes

Juyoung Park (SOUTH KOREA)

Title: How to Meet Your Voice

Duration: 30 minutes

In How to Meet Your Voice, Korean deaf artist Park Ju-Young transforms “care” into an ethical practice of perception. She invites audience members to write their names on her body, records their voices, and uses sponge-and-amplifier interactions to transfer the ink impressions of sound onto yellow cards, which are then distributed to participants. Through this sequence, auditory experience becomes visible and tangible, fostering an understanding of perceptual differences and enabling empathetic engagement. Park’s body becomes a site of shared sensibility, transforming auditory absence into the possibility of communication. Here, care manifests as recognition of and repair for perceptual gaps.

Where Mezzetti and Park translate care into practices of emotional and empathic engagement—through religious ritual and sensory difference, respectively—artist Christine, in Fancy Life, extends care to the ecological and life-community dimension. Her performance, focused on dispersal, aggregation, and regeneration, constructs a materialized vision of care as ecological ethics. Dressed in a green gown, Christine becomes an extension of nature and a mediator of affect. Through gentle touch, guidance, and wrapping, she reorganizes bodily distance into a network of tender relations. The web-like structures symbolize connection, protection, dependency, and vulnerability, forming a tangible “net of care.” Christine’s non-coercive actions replace verbal commands, presenting care as a socially generated relation arising from bodily rhythms and shared presence. When participants curl into fetal postures under her touch and gradually awaken, individual vulnerability, awareness, and regeneration are embodied as a parable of life cycles. Christine’s “chromatic” body, glowing in green light, signifies the regenerative energy of nature, transforming care from mere emotional provision into a mutually generative life force. Discarded plastic bags from consumer society are imbued with memory and shelter, expanding care beyond human recipients to objects and the environment. At the performance’s conclusion, Christine collects the scattered plastic bags, completing an act of gentle labor that recycles and repairs the world, extending care from ritual gesture to ongoing ecological practice.

Christine Straszewski (GERMANY)

Title:FANCY LIFE

Duration: 30 minutes

Conclusion

Looking back on the 13th UP-ON International Live Art Festival, it may be more apt to understand it as a “thought experiment in presence.” The artists used their bodies as mediums to continuously question multiple realities: How can action become knowledge? How does the “live site” generate meaning? From Hu Yingchao’s self-interrogation forced against a wall, to Deej and Vichukorn Tangpaiboon’s cries across social fissures, to Christine, Mezzetti, and Park Ju-Young rebuilding connections between humans and the world through “care,” all performances together constituted an open field of perception. This space gathered individual experience while echoing social memory.

In this sense, the UP-ON International Festival can be seen as a dynamic formation composed of difference, conflict, and resonance. Each performance acted as a node, where art ceased to be merely an object to be viewed, becoming instead an act of reflection, an experiment in emotion, and a practice of community. Even after the festival lights dimmed and the spaces fell silent, the reverberations of presence persisted. They remind us that the meaning of performance art never concludes within the work itself—it continues to resonate in the ever-emerging “here and now.”

LIU Guicheng (Researcher)

LIU Guicheng is a doctoral candidate in Art Theory at the School of Arts, Peking University. He received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the School of Literature, Nankai University. His research focuses on theatre and performance studies, with academic interests covering performance theory, performance philosophy, and cultural performance. His research approach emphasizes interdisciplinary dialogue, attempting to explore how performance can serve as a form of social practice and cultural criticism at the intersection of sociology, anthropology, and performance studies. In the field of performance philosophy, he is particularly interested in how performance can generate the same level of critical power as philosophical thinking, with a special focus on the interaction between performance and political philosophy. In the context of the Global South, he examines cultural performances as social movements within Asia and their inter-Asian networks, considering their potential in shaping the public sphere. His related works have been published in journals such as Drama, Theatre Arts, NJU Drama Review, and Asia-Pacific Studies, etc., with representative papers including The Contemporary Presentation of the Relationship between Human and Puppets, The Politics of Memory in Myanmar Performance Art, and The Theatrical Imagination of Anthropology, etc.